When the Mills College Art Gallery opened its doors in 1925, its inaugural collection consisted primarily of works by contemporary Bay Area artists. Today, the Art Museum still prioritizes the work of living artists, and the collection continues to reflect vibrant and diverse artwork from the Bay Area as well as more national and international perspectives.

Works in the collection demonstrate the myriad ways artists represent and reflect our local communities as well as highlight the Bay Area as a site of resistance, abundance, and celebration. Craig Calderwood’s tapestry, Pig Hair Sword, 2022, helps epitomize this theme. Created while an artist-in-residence at the museum, the piece is deliberately made from what would typically be considered “low-end” materials, such as fabric sourced at a thrift store and dimensional paint often used for children’s crafts. Their work is deeply autobiographical, offering a reflection on their childhood experiences and their identity as a queer and trans person. Calderwood delves into concepts of gender fluidity, desire, biodiversity, and otherness through their portrayal of androgynous figures and body parts that possess unfamiliar qualities.

This effect is amplified by elaborate and highly detailed patterning, effectively concealing any discernible secondary sex characteristics and encouraging what Calderwood describes as a sense of “genderlessness.” Calderwood’s distinct vocabulary of symbols and patterns seen throughout their work is rooted in the coded languages historically used by queer and trans communities, and is informed by extensive historical research, personal narratives, and pop-cultural moments.

Currently residing in Oakland, California, Adrianna Adams is a painter and printmaker whose work explores identity in relation to issues of race, gender, and representation. Weekly Routine #1, 2020, depicts the work of Black hair care as a form of art, social practice, and self- and community-care. Like the work of American artists Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson, Adams examines Black hair to analyze race, gender, and class, as well as to reveal assumptions and biases around certain styles of hair. Abstracted into an interwoven tapestry of braids and barrettes, Adams’ image serves to reclaim the Black female body while subverting cultural stereotypes. The print was brought into the museum’s collection through a student acquisition project in which students identified, researched, and justified specific artworks to help diversify the museum’s permanent collection.

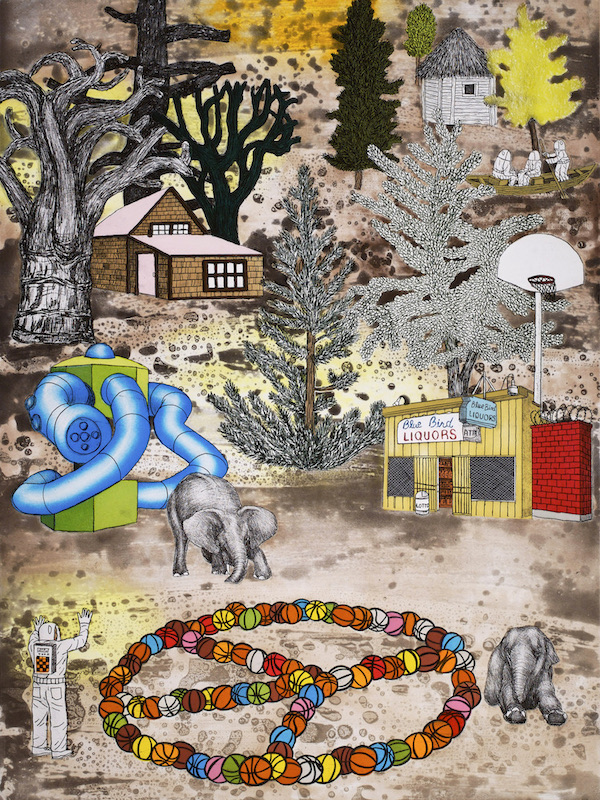

David Huffman’s paintings and prints also serve as allegories of the Black American experience, depicting stereotypical signifiers of this history in order to reclaim them. A Berkeley-born painter, installation artist, and educator, Huffman is known for works that combine science fiction aesthetics with a critical focus on the political exploration of identity. His work includes Black space travelers he calls “traumanauts,” who Huffman describes as searching for a different sense of self and location stemming from a historical homelessness that began with the dislocation of slavery.1 These figures enter futuristic landscapes where paint combines with images of cosmic debris and ecological decay. His print Ouroboros, 2007 combines many of Huffman’s recurring images, such as his space-suit protected traumanauts navigating the flooding of Hurricane Katrina, basketballs in the shape of a peace sign as a positive symbol of Black American life, and references to homes–in this case depictions of a traditional African hut and a wood-shingled Craftsman bungalow common in Berkeley.

History, memory, tradition, migration, and social justice are subjects explored by Chinese-born American artist Hung Liu. Her paintings often incorporate unidentified figures from historic photos with the intent of uplifting and empowering these individuals—frequently women and girls—by surrounding them with auspicious Chinese motifs. In White Rice Bowl, 2014, Liu based the image of a child with bound feet tenderly feeding her younger brother on a 19th-century photograph by Frank Cannaday. Foot binding in Chinese society was primarily done to conform to beauty standards, enhance social status by indicating wealth and leisure, and restrict women’s mobility. Young girls’ feet were broken and tightly bound to dramatically alter their shape and size, resulting in lifelong disabilities in pursuit of cultural standards of feminine beauty. Liu often painted from historical photographs, using washes and drips to visually dissolve the images. In doing so, she hoped to wash the subject of its exotic “otherness” and give vibrancy and new life to those forgotten.

Liu created White Rice Bowl in collaboration with master printer David Salgado at Trillium Graphics. Together, they developed an elaborate process to create mixed-media works combining aspects of painting, printmaking, and photography that allowed Liu to revisit and enhance elements from her paintings and embed them in layers of translucent resin. The glowing gold leaf background invokes gilded Byzantine paintings, suggesting immortality and spiritual transcendence for Liu’s subjects.

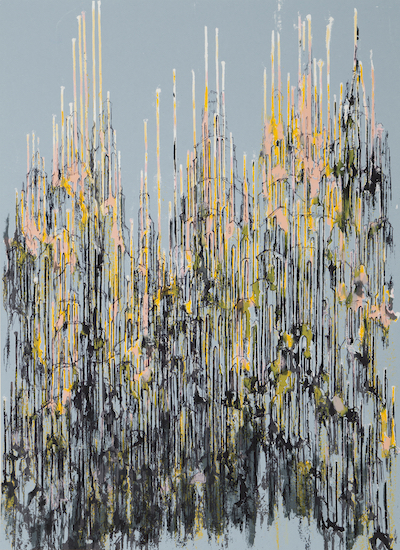

The subjects of power and wealth are imbedded in Diana Al-Hadid’s work as well. Born in Aleppo, Syria, Al-Hadid emigrated with her family to Ohio at the age of five. Her sculptures and prints, such as We Will Control the Vertical, 2009, draw inspiration from both ancient and modern civilizations, including art historical religious imagery, ancient manuscripts, and medieval architecture. Inspired by historical forms from art and architecture, Al-Hadid’s works are charged with drips, textures, patterns, and ornaments that recall Arabic calligraphy and Islamic textile patterns. The works have been described as metaphorical “bridges” between the past and the present, as well as cultural bridges between the Middle Eastern world of Al-Hadid’s early childhood and the Western world she now inhabits.

Al-Hadid incorporates towers as a recurring theme in her work, utilizing stylistic elements from a variety of incongruous periods, from Gothic churches to futuristic skyscrapers. By re-imagining the monuments of great civilizations as fading images or apparitions, Al-Hadid challenges the viewer to question established notions of both Western and Eastern cultures, rendering these symbols of power as mysteriously inscrutable and full of new possibilities.

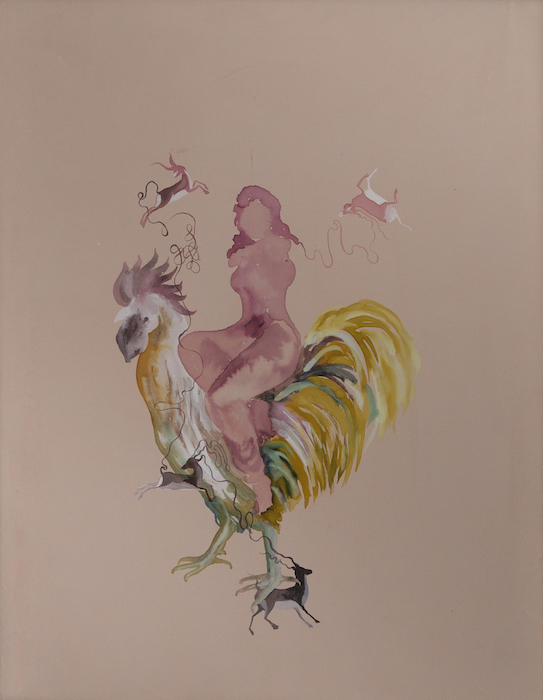

Inspired by the highly ornate traditional Persian and Indian styles of painting, Shahzia Sikander’s miniature works also blend both Eastern and Western aesthetic traditions. Born in Pakistan, Sikander studied traditional Indian miniature painting before coming to the United States. Once here, she began to layer loosely painted symbols based on Hindu and Western imagery onto her miniatures, creating multifaceted works that reflect her cultural and feminist perspectives. Her work investigates issues surrounding migration, borders, and the subversion of Western stereotypes of South Asian women.

Plush Blush, 2003, is part of a body of work using fluid inks and washes on clay-coated paper. The imagery is inspired by the composite tradition of miniature painting, in which multiple creatures are joined together to create the shape of an animal. Like Hung Liu, Sikander’s work is rooted in a lexicon of recurring motifs that makes visible marginalized subjects, often reflecting on her own experience as an immigrant and diasporic artist working in the United States.

Like Sikander, Rina Banerjee’s work focuses on ethnicity, race, migration, diaspora, and her own personal experience as an immigrant while fusing various cultural inspirations such as Indian miniature paintings, Chinese silk paintings, and Aztec drawings. Banerjee frequently places her subjects in fantastic landscapes that are in a state of transformation and that feature creatures which appear to be hybrids of birds and beasts.

Her print Dangerous World, 2010, serves as a family portrait, picturing the artist, her husband, and their daughter in the lower foreground. In this work, which Banerjee created during her struggle with cancer, the artist addresses the fragility of life and her fight for survival. Rendered as amorphous figures floating in space, her demons are foreboding and ominous. Using ink and highly absorbent paper, Banerjee allows colors to bleed into one another, creating a tie-dye effect—evoking the traditional Indian tie-dye technique Bandhani, and, perhaps, the fluidity of life. For the artist, her work “depicts a delicate world that is also aggressive, tangled, manipulated, fragile, and very, very dense.”2

The Mills College Art Museum supports contemporary artists—whether local or international-whose creative visions often come from personal experiences, perspectives, and narratives, thus providing meaningful ways to experience and understand the diversity and complexity of the world we live in.

NOTES