The Bay Area has long been a center of ceramic innovation, and the Mills College Art Museum’s collection reflects the groundbreaking ceramics program on this campus and throughout the region—from traditional, to modernist, to experimental styles. The museum has collected and shown ceramic works since the 1930s, a curatorial and collecting focus that became more developed with the founding of the Mills College Ceramic Guild in 1942.

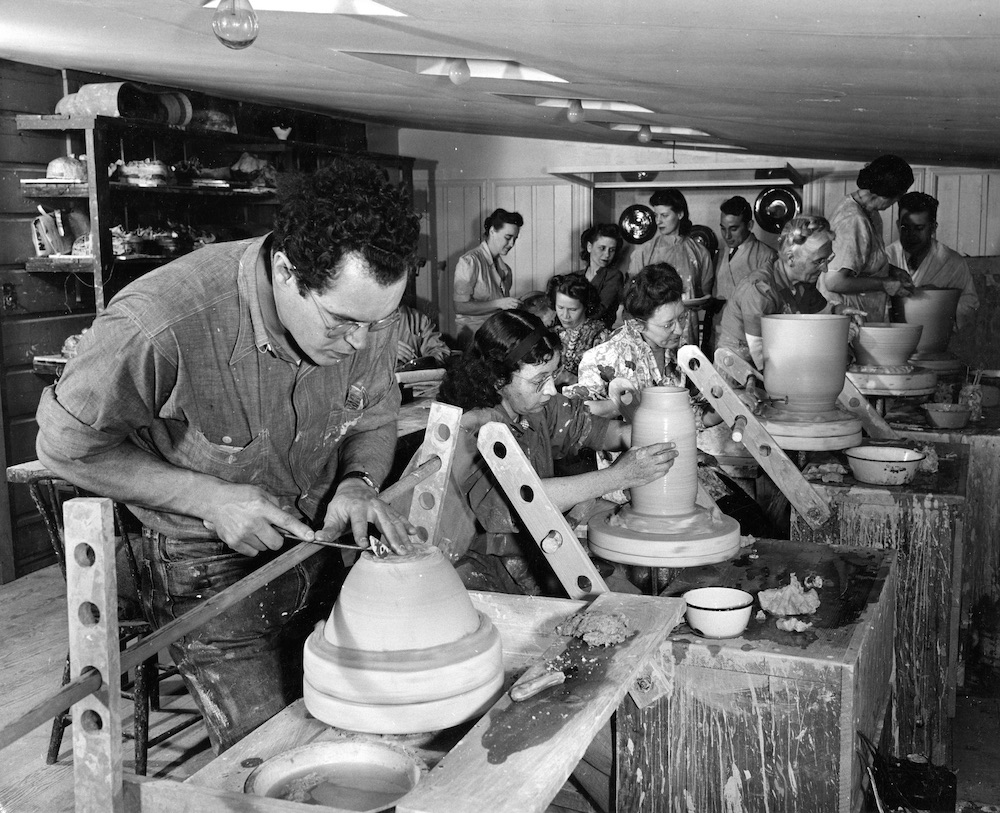

The Guild was established by a group of students who were enrolled in the summer pottery program at the College but wanted to be able to work year-round. They proposed a deal: in exchange for studio time and space, they would upgrade and maintain the shop facilities without interrupting the work of Mills students. Carlton Ball, Professor of Ceramics and chairman of the art department, agreed to the arrangement and became an honorary member of the Guild. Among the original Guild members were Elena Netherby, Helen Mitchell, Ruby O’Burke, Nancy Alexander, Esther and Fenner Fuller, and Antonio Prieto, a group of both established and emerging Bay Area artists interested in modernist ideas. Conceptually, the Guild paralleled the emergence of cooperative potteries on the East Coast in the 1920s and 1930s. Like the Mills College Ceramic Guild, these potteries were founded and operated mostly by women, produced popular decorative wares, and were committed to the advancement of technical skills and research in the ceramic arts. This surge in “art pottery” served as a foundation for the American modern ceramic movement.

During the 1950s, the field of ceramics experienced a schism between craft and art. While some potters continued to adhere to the conventional ideas of beauty and form, others asserted independence in search of a new aesthetic vocabulary. The catalyst of this shift was Peter Voulkos, whose radical work attracted a dynamic group of artists who incorporated influences from jazz music, Beat poetry, and Abstract Expressionist painting. This new attitude in clay sculpture, indigenous to California, became a major turning point for American ceramics.

In the mid-1960s Voulkos moved to Berkeley and his influence spread to another group of individualist students including Jim Melchert, Bob Arneson (who received his MFA at Mills), and Ron Nagle (a Professor of Ceramics at Mills). Local ceramic leaders and strict traditionalists like Herbert Sanders and to some extent Mills faculty member Antonio Prieto, seemed to represent the end of an era for intimate college pottery programs.

At Mills, Prieto was responsible for establishing both the advanced undergraduate and graduate levels of studio art study and for opening up the graduate program to men. An international advocate in the crafts movement, he instilled a sense of professionalism and a strong work ethic in his students—a quality that Arneson learned and used in his own work.

Prieto realized the value in collecting other ceramists’ work for study purposes and began gathering pieces while a member of the Mills College Ceramic Guild. Later, as a faculty member in ceramics at Mills (1950-1967), he began to collect for the Mills College Art Gallery, amassing a personal collection of extraordinary breadth, including works by Voulkos, Arneson, Viola Frey, and Nancy Selvin. Upon his death in 1967, and the subsequent disbanding of the Guild, most of the collection was amassed by Eunice Prieto, his wife and coworker. She personally contacted the many potters and sculptors who had known or worked with Prieto asking them to commemorate his death. Ceramicists sent examples of their work, and others made a donation to the Antonio Prieto Memorial Purchase Fund.

Eunice Prieto also approached Easton Rothwell, president of the College during the 1960s, about finding space in the newly planned Rothwell student center to exhibit the Prieto Collection. Previously earmarked as a dressmaking and beauty shop, an extension of the center was designated as the Antonio Prieto Memorial Gallery for the purpose of exhibiting Bay Area ceramics.

The resulting Prieto Collection consists primarily of work made in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s by former graduate and undergraduate students, instructors and visiting artists in the Mills ceramic department, with additional work given by ceramists unrelated to Prieto or the College. Many pieces in the collection reflect the artists’ early efforts in clay, illustrating an art era from approximately 1950-1980. As a group, the collection has important historical references to styles, people, attitudes, technical achievements, methods of instruction, and international influences.

The Prieto Collection is complemented by the Herbert Sanders Collection of Japanese Folk Ceramics at MCAM. Sanders is best known for his definitive work developing crystalline glazes, which he applied to his traditional porcelain forms and for his book The World of Japanese Pottery (1967) written in collaboration with Japanese potter Kenkichi Tomimoto. As a Fulbright research scholar in ceramic art and education, he spent 1958 traveling throughout Japan interviewing and observing potters, recording their ceramic processes.

In 1976 Sanders donated a sizable collection of antique and 20th-century Japanese pottery to the museum, with works by modern Japanese masters such as Shōji Hamada and Kanjirô Kawai (co-founders of the Japan Folk Art Association). Although these artists were inspired by the mingei (Japanese folk art) traditions of their country, their influence extended beyond Japan to such notable Western ceramic artists as Bernard Leach.

Hamada and Leach visited Northern California and Mills College in 1953, igniting a charged dialogue regarding the future of studio pottery in the face of a growing interest in radical sculptural form on the West Coast. The tenets of their work include using locally available materials, making simple useful pots in large quantities by hand, working communally, and selling pots inexpensively; allowing for producing the highest possible aesthetic and spiritual values. Mingei influence is apparent in the American ceramics that comprise the Prieto Collection as well.

Ron Nagle brought a new era of experimentation to the college’s ceramics program, as Professor at Mills College from 1978-2010. Internationally recognized for his unique ceramic sculptures, Nagle’s work helped advance clay from the world of handicraft to that of sculpture. Numerous examples in MCAM’s collection demonstrate how Nagle’s work ironically maintained a formal relationship with the traditional cup form while incorporating contemporary American popular iconography, lavish color, and painterly attention to surface.

In addition to the museum collection, this interest in experimental ceramics continues in our exhibition program. The exhibition Kari Marboe: Duplicating Daniel (2020) traced Marboe’s attempts to recreate an original sculpture, recorded as missing from MCAM’s permanent collection, by the influential but under-recognized ceramicist Daniel Rhodes. Using data collected from research in the museum’s archives and descriptive information mined from interviews with artists and anecdotes from peers in the field of art, the exhibition included Marboe’s numerous attempts to create physical “replicas” of Rhodes’ sculpture including hand-built objects, 3-D printed ceramic models, and written descriptions from colleagues. Ultimately, the museum acquired two of Marboe’s pieces as “replacements” for the missing Daniel Rhodes sculpture, demonstrating the generative possibilities of collection and exhibition archives through the medium of clay.