Originally founded to serve an undergraduate women’s liberal arts college, the Mills College Art Museum has had a long-held mission of supporting the work of women artists through commissions, exhibitions, and collecting. From its beginning, the museum collected and championed Bay Area modernist painters and sculptors, including significant women artists whose influence was felt through their experimentation in form and media, as well as through their teaching. Among these notable artists were Anne Bremer, whose prize-winning still-life and landscape paintings combined elements of vibrant Post-Impressionist color and linework, and sculptor Adaline Kent, whose forms were inspired by the natural landscape of Northern California.

Acknowledgement is certainly owed to Contance Jenkins Mackey, the co-founder of the Spencer Mackey Art School in 1916 (which later became part of the renowned San Francisco Art Institute), who played a key role in popularizing modernist European painting styles on the west coast and whose influence is seen in paintings from the museum’s inaugural collection.

In the early 20th-century, the Bay Area was a center of photographic innovation and MCAM was an early supporter of photography as an important art form and the numerous women who were essential to the establishment of a new modernist aesthetic of photography. One of the best-known examples is Imogen Cunningham, who is famous for her botanical photography, nudes, and industrial landscapes.

She was a key member of the California-based Group f/64, praised for its dedication to the sharp-focus rendition of simple subjects. During the 1920s and 1930s, Cunningham served as the Mills College campus photographer and was married to Roi Partridge, the first director of the Mills College Art Museum.

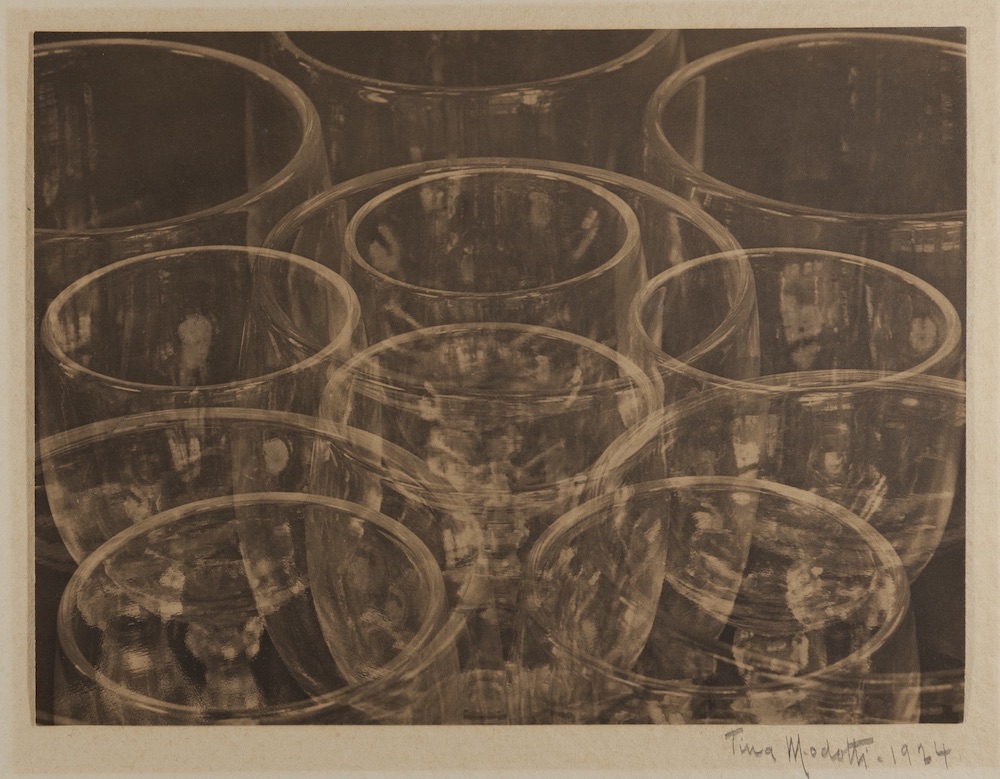

Within their circle of artist friends was photographer Tina Modotti, known for her skillful use of composition and shadow. Her most famous images captured the milieu of Mexico City between the first and second world wars, including portraits of artists such as Frida Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera. Her double exposure image in MCAM’s collection, Experiment in Related Form, is a stunning photographic print donated by Partridge in 1926.

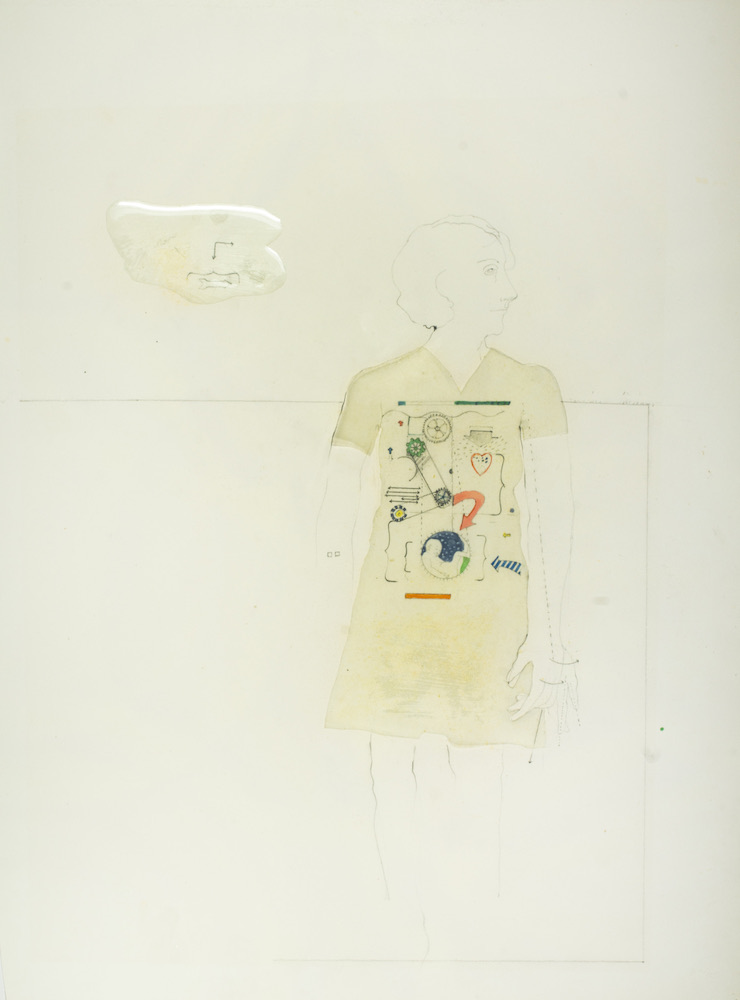

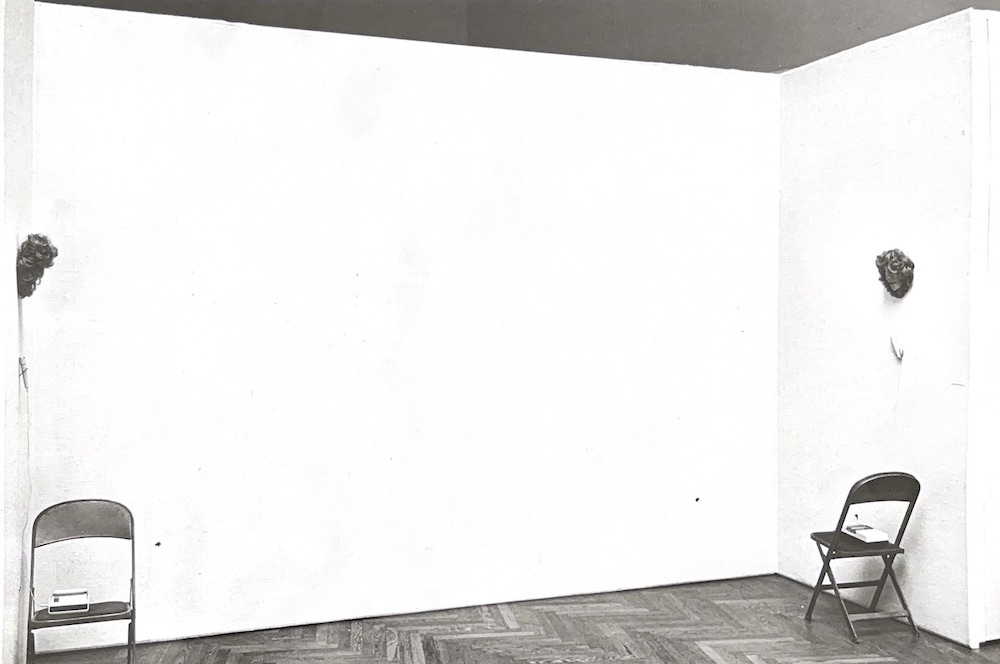

Unsurprisingly, MCAM was an early supporter of feminist art movements. In 1973, interactive media art pioneer Lynn Hershman Leeson, had an exhibition showcasing feminist conceptual work engaged with technology, cybernetics, and the female body. Among her exhibited drawings and sculptures was an early sound installation, Conversation Piece (1972), featuring masks of human figures conversing via tape recorders with the viewer. As part of her work, she designated a quarter of her space to then aspiring filmmaker Eleanor Coppola, who created her first publicly presented video piece, a portrait using Hershman as her subject.

In 1975, the museum presented a retrospective of works by Miriam Schapiro, whose large-scale collages and paintings raise the issue of feminism and art, and specifically, feminism in relation to abstract art. Schapiro was known for her vibrant, geometric quilts and her minimalistic abstract paintings. Her work often tackled feminist issues through tradition crafts, work which was historically associated with women and often devalued by the art world, elevating “woman’s work” to the status of high-art.

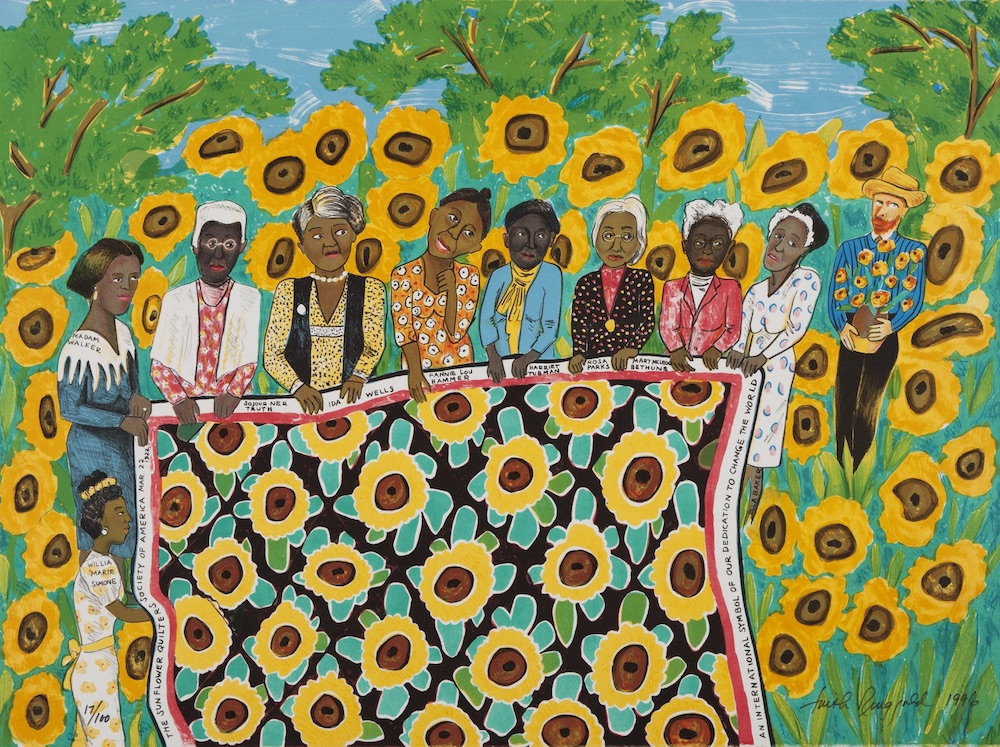

Throughout the latter half of the 20th-century, the museum continued prioritizing feminist perspectives while specifically supporting the work of international women and artists of color, a priority that continues today. In 1992, MCAM hosted Faith Ringgold’s twenty-five year survey featuring her narrative quilts that document her departure from Western traditions of fine art and craft, to her embrace of family and cultural heritage. Heavily influenced by the Civil Rights and feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, Ringgold’s political activism against racial and gender discrimination is reflected in much of her work, including pieces in MCAM’s collection.

That same year, French photographer and conceptual artist Sophie Calle was a visiting professor of French Studies at Mills College. Creating work that frequently depicts human vulnerability while examining identity and intimacy, she exhibited a series of large-scale photographs called Les Tombes (Graves, 1990/1991). Featuring images of gravestones found in a cemetery in Bolinas, California, the only inscriptions depicted in the photographs are words that describe family connections: mother, father, son. Through the work, Calle’s encounter with this site is transformed into a conceptual reflection on themes such as death, mourning, and family relationships during the period of the AIDS epidemic.

The theme of migration and displacement is inherent in the work of Indian American printmaker Zarina, whose work was featured in her ten-year survey, Mapping A Life, 1991-2001, curated by art historian Mary-Ann Milford.

Informed by her identity as a Muslim-born Indian woman, as well as a lifetime spent traveling throughout the world, she uses visual elements from Islamic decoration, especially the regular geometry commonly found in Islamic architecture. Her minimalist works on paper and sculptures document her peripatetic lifestyle and complex notions of what makes a place home.

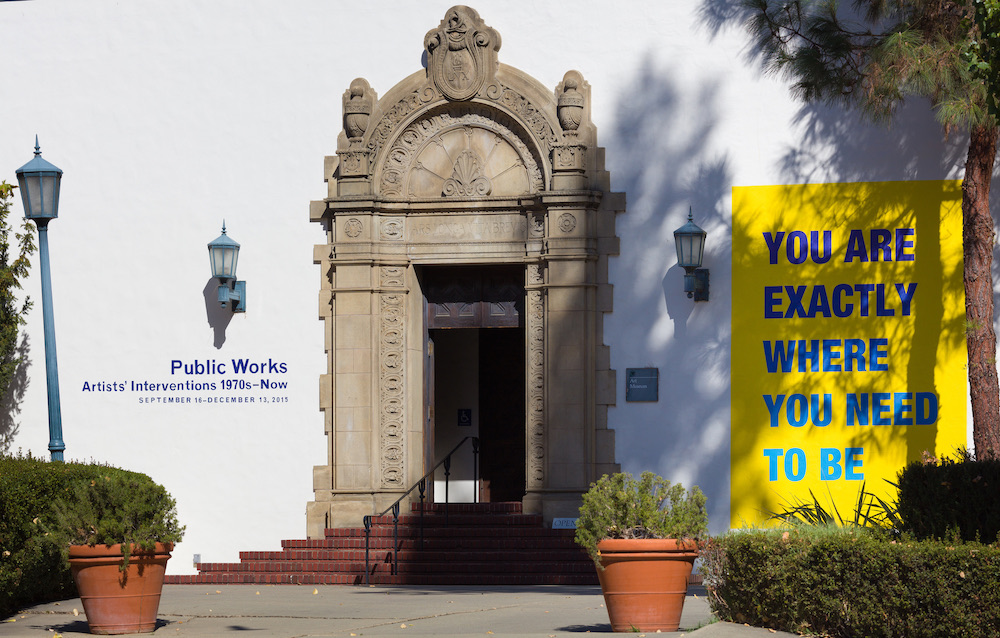

Throughout the past two decades, the museum has used its gallery as a laboratory space for curators and artists to create new work and explore issues pertinent to the 21st-century. Public Works (2015), curated by Christian L. Frock and Tanya Zimbardo, examined strategies of public practice by women artists from the 1970s to the present.

The exhibition showcased important historical and contemporary projects that explored the inherent politics and social conditions of creating art in public space.

From Bonnie Ora Sherk’s early environmental sit-ins to Susan O’Malley’s posters giving advice from strangers, the work in the exhibition moved beyond traditional views of public art as monumental and/or permanent artworks and instead focused on often small but powerful temporary artistic interventions online and in the urban environment.

MCAM has also used its exhibition program to realize major artist projects, including Cuban American artist María Elena González’s Tree Talk.

Exploring the translation between the physical and the acoustical, Tree Talk investigated the unexpected visual parallels between the bark of birch trees and cylindrical player piano rolls. González transcribed the distinctive bark pattern from three birch trees found at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, and each tree yielded unique compositions for the player piano. Visitors were able to “hear” each tree through live and recorded player piano performances.

Related drawings, prints, videos, and sound installation were also featured in the exhibition, demonstrating González’s interest in both representations of sound as well as sound as a sculptural material. In addition, the artist worked closely with graduate experimental music students to develop two live performances using drawings of the tree bark as graphic scores.

Similar in scale, Archæology in Reverse presented a series of new, immersive site-specific installations and photographs developed by Catherine Wagner, long-time professor of photography at Mills College. The exhibition highlighted the extraordinary architectural space of the museum through sculptural installations, site-specific interventions, photographs, and documentation of site-specific choreography by dance faculty member Molissa Fenley.

As a photographer long interested in the phenomenon of light, Wagner examined the possibilities of physically transforming the museum’s ceiling and gallery walls into a series of apertures. Her project revealed the museum’s usually hidden, glass-roofed skylight enclosure with the use of large periscopes that both project and reflect elements within the ceiling.

Penetrating the gallery’s perimeter, Wagner revealed previously covered windows and doorways, bridging interior and exterior space. The addition of colored acrylic accentuated the inherent geometry of these spaces, focusing the eye and creating order within the chaotic layers of architectural history embedded in the building.

Wagner’s exhibition explored the museum’s role as a cultural, social, and experiential lens, serving as an apt metaphor for how it refocuses the viewer’s attention and experience. By developing interdisciplinary collaborations and generating new ideas around experimentation with materials and space, the museum’s exhibitions and collections change the way we see, particularly through the lens of women artists.