One of the leading patrons of the arts in San Francisco in the 1920s and 1930s, Albert M. Bender was an Irish American art collector who played a key role in the early career of photographer Ansel Adams and was one of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera’s first American patrons. He had a significant impact on the cultural development of the San Francisco Bay Area by providing financial assistance to artists, writers, and institutions. As a Trustee of Mills College, he was the lead founder of the Mills College Art Museum in 1925.

Bender collected art with an emphasis on work by local Bay Area artists and the art of China, Japan, and Tibet. In addition to their inherent beauty, Bender hoped that Asian art objects would help inspire greater understanding and tolerance of California’s Pacific neighbors. His generosity includes over 200 Asian items gifted to the museum, including textiles, wood-block prints, and a distinctive pair of marble Chinese guardian lions that have greeted visitors to the campus art complex since 1933.

Building on Bender’s initial gift, the museum has built a significant collection of Japanese and Chinese textiles, the most important being the Shojiro Nomura Fukusa Collection. A connoisseur of Japanese textiles, Nomura’s personal collection was presented by his son to Mills College in 1953 while his granddaughter Betty Nomura was a student at Mills. This collection of Japanese gift covers—or fukusa—dates to the Edo period (1615-1867), a time when textiles were an integral part of Japanese art with no arbitrary division between what was considered fine and decorative arts. Eminent artists were commissioned to design textiles and each work was an original creation.

The fukusa in this collection are ingenious works of art incorporating a wide variety of techniques, including embroidery, painting, and dying. Fukusa can be considered a prototype of modern greeting cards. Square pieces of lined fabric, they were simply laid over a gift and decorated with motifs chosen to indicate either the purpose of the gift (a birth, a marriage, etc.) or because they are appropriate for one of the annual festivals when gifts are exchanged. The richness of the decoration of the fukusa attests to the giver’s wealth, its design reflects his scholarship and aesthetics, and his cultural sensitivity is judged by the suitability of the fukusa for the occasion.

One of the finest examples in the collection depicts Chinese children chasing butterflies. The interest in Chinese philosophy and poetry reached its peak in Japan in the mid 1700s, when this fukusa was created. These karako, literally Chinese children, were used much in the same manner as Western artists used the image of the cherub. Chasing butterflies symbolizes the attainment of manhood, and this fukusa would have been given as a gift at The Thirteenth Year Ceremony. The six butterflies on this fukusa likely refer to a court dance, Kocho no Mai, which was performed by six young women costumed as butterflies. The large amount of gold-wrapped thread on the fukusa is visual evidence of the affluence of the giver, and the extremely fine embroidery used in the patterning of the costumes depicted in this scene is among the finest in the collection.

In addition to holdings from a large range of Asian cultures and time periods, the museum’s collection and exhibition history has included a focus on local Asian American artists from the very beginning. Early examples include the work of Dong Kingman, a Chinese American artist and a leading watercolorist. Born in Oakland in 1911, he avidly documented San Francisco’s Chinatown in the early 20th-century with images characterized by bold color and broad brushstrokes. He is known for his urban paintings and was one of the few known Asian American artists to work in the 1930s for the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression, examples of which are in the museum’s collection.

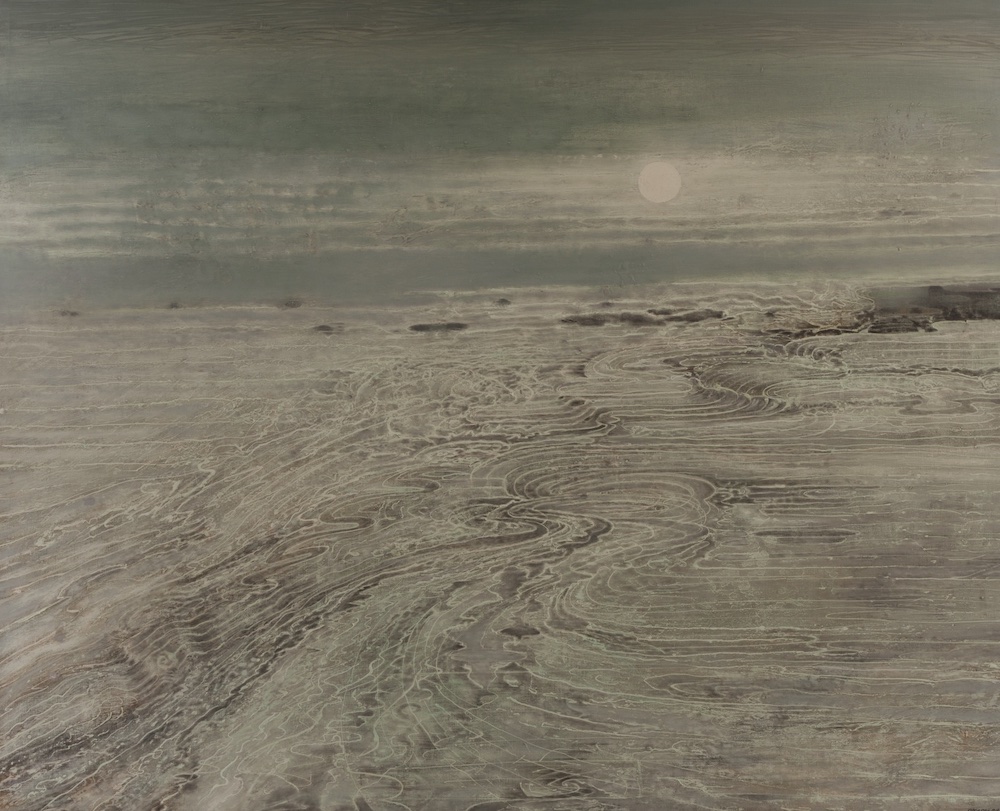

The museum also supported the work of Chiura Obata and Arthur Okamura, Japanese American artists active in the Bay Area during the first half of the 20th-century. The incredible landscape of Northern California served as an important source of imagery for both, and both were involved with ecological movements and the protection of national park systems. Known for his screen printing and expressionistic paintings, Arthur Okamura was a Japanese American artist who rose to prominence in the 1960s as a book illustrator and member of an artist community based in Bolinas, California. As a child during World War II, Okamura and his family were forced to relocate to a Japanese American internment camp in southeast Colorado. His painting Reef/Moon is typical of Okamura’s use of abstracted, Surrealist-inspired depictions of landscapes, particularly water views. The layered pattern of ocean waves and romantic moonlit sky create a dream world that Okamura referred to as “ghost waves.”

Obata was one of the most significant Japanese American artists working on the West Coast in the last century. Born in Okayama, Japan, Obata emigrated to the United States in 1903 and embarked on a seven-decade career that saw the enactment of anti-immigration laws and the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. He emerged as a leading figure in the Northern California artistic community, serving not only as an influential art professor at UC Berkeley for nearly twenty years, but also as a founding director of art schools in the incarceration camps. Obata is best known for majestic views of the American West, sketches based on hiking trips throughout Northern California to capture what he called “Great Nature.” His work is grounded in close observation, rendered with calligraphic brushstrokes and washes of color, and he saw California’s landscape as a site for the exploration of identity, spirituality, and bodily sensation.

More recently, the museum’s exhibitions have continued to showcase narratives focused on Asian American experiences in the Bay Area. The 2013 exhibition Hung Liu: Offerings featured the work of Chinese-born painter Hung Liu, a long-time painting faculty member at Mills College known for championing the stories of often marginalized migrant communities. The museum recreated her monumental installation Jiu Jin Shan (Old Gold Mountain), in which Liu used over two hundred thousand fortune cookies to create a symbolic gold mountain that engulfs a crossroads of railroad tracks running beneath. The junction where the tracks meet is a visual metaphor for the cultural intersection of East and West as well as for the end of dreams of many Chinese immigrants who perished during the building of the transcontinental railroad in the United States.

Through the work, Liu references not only the history of the Chinese laborers who built the railroads to support the West Coast Gold Rush, but also the specific history of San Francisco. The city was named Old Gold Mountain by the Chinese migrant workers in the 19th-century as an expression of the hope, shared with so many other new arrivals, to find material prosperity in the new world. The fortune cookies become a substitute for gold nuggets as well as for the traditional Chinese burial mounds of Liu’s Manchurian relatives.

Photographer Binh Danh’s work also brings to light the complicated history of Asian and American cultural confluence by investigating his Vietnamese heritage and our collective memory of war. Danh immigrated from Vietnam with his parents to San Jose in 1979. Although too young to remember the horrors of the Vietnam War, his images evoke the death, loss, and trauma his family experienced through his choice of haunting imagery that represent his family history. His exhibition Collecting Memories featured his Military Foliage series, a large installation of military camouflage designs imbedded into actual foliage.

Danh utilizes a specific organic technique of his own invention to create these prints, producing a chlorophyll print that embeds photographic images onto leaves through photosynthesis. Danh also captured the aftermath of the American-Vietnam War through daguerreotypes, one of the oldest forms of photography dating back to the 19th-century. The daguerreotype is a process in which an image is formed on a metal plate through exposure to light and can easily be wiped away if not encased in glass. The beauty of the daguerreotype, both aesthetically and metaphorically, speaks to the fragility of history and memory.

With Asian Americans comprising over thirty percent of its population, the Bay Area is home to one of the largest concentrations of Asian American and Pacific Island people in the country. In 2021, this population witnessed a dramatic spike in violence directed at elderly Asian Americans during the COVID pandemic. Responding to this growing epidemic of violence, MCAM artist-in-residence Christy Chan created Dear America, a guerilla public art project which projected the artwork of six Asian American artists onto the walls of high-rise buildings throughout the Bay Area.

A film director and visual artist, Chan uses storytelling and community organizing to create dialogue around race, class, and social justice issues. The 4 to 15-story tall projections beamed images and messages of resilience in English and eight different Asian languages, including, among others, Chinese, Taiwanese, Japanese, and Thai. With a few exceptions, the projections were unsanctioned and intentionally installed without gaining permission from municipalities and local corporations. Dear America was an artist-run project supported by community donations and community partners such as the Mills College Art Museum, the non-profit organization Stand With Asian Americans, and the Chinese Historical Society of America in San Francisco.

Recognizing the history of our location as part of the Pacific Rim and the rich cultural diversity of Northeastern University’s community, the museum continues to prioritize the work of Asian and Asian American artists and the narratives that they engage with.