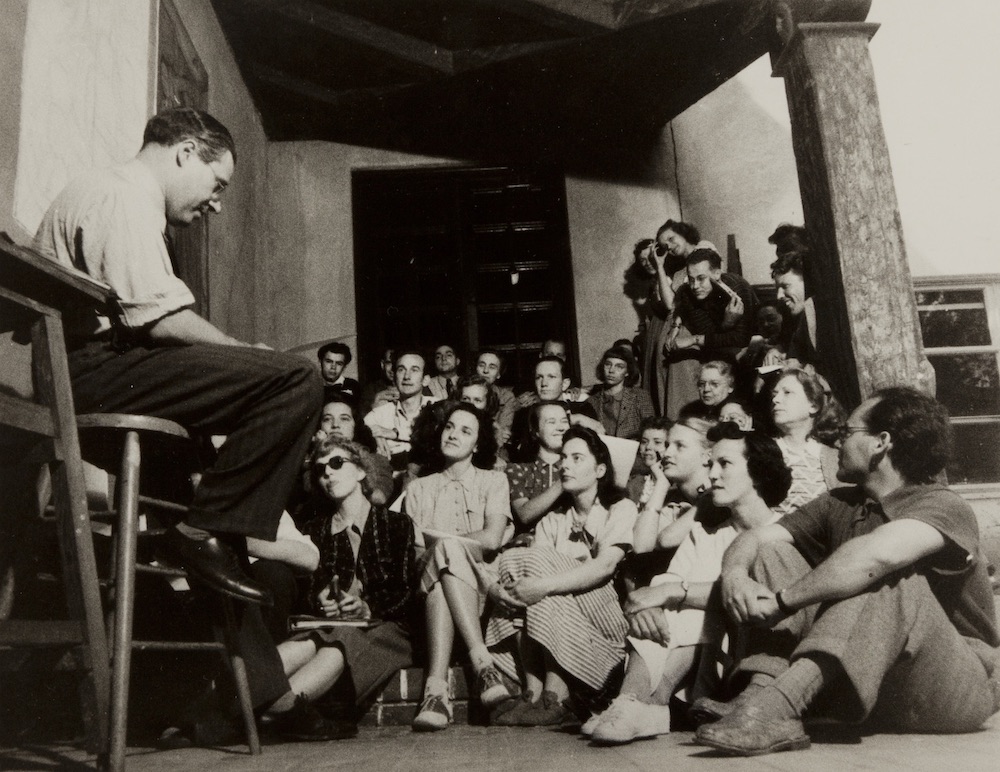

The Mills College Art Museum has a long and storied history of artistic innovation, inspiring and educating generations of students and community members alike. From 1933 to 1952, under the direction of esteemed German art historian Dr. Alfred Neumeyer, the Art Museum participated in the “Summer Sessions,” organized through the leadership of Mills College President Aurelia Henry Reinhardt. The Summer Sessions were a series of co-educational classes and workshops, open to students and the public, in a variety of disciplines, including studio art, music, French, sports, creative writing, modern dance, and child development. Over its lifetime, the program hosted an eclectic mix of renowned European, American, and Latin American artists to teach, exhibit, and celebrate their groundbreaking work.

Neumeyer and his predecessor Roi Partridge were trailblazers in the visionary curation of avant-garde artists for the program, showcasing luminaries such as Alexander Archipenko, Lyonel Feininger, Fernand Léger, László Moholy-Nagy, and Max Beckmann.

The Summer Sessions program carved out a critical space for expression, reflection, and deliberation within and in response to the complex historical, political, economic, and cultural conditions of the period. Following the 1933 assumption to power of the National Socialists in Germany and the subsequent attack on modernism, artists, writers, critics, curators, and countless other creatives found themselves subject to much unwelcome scrutiny because of their political, ideological, and aesthetic commitments. While American immigration policy at the time was shaped by nationality quotas set down in the National Origins Act of 1924, teachers in higher education were able to obtain “nonquota” visas that justified to European authorities the teachers’ urgent need to flee Europe. Neumeyer, himself, was a refugee scholar in art history when he was offered the position as director of the Mills College Art Museum in 1935. Intimately involved with the art scene in Berlin, Neumeyer offered teaching opportunities to fellow European artists who were trying to escape the traumas of World War II.

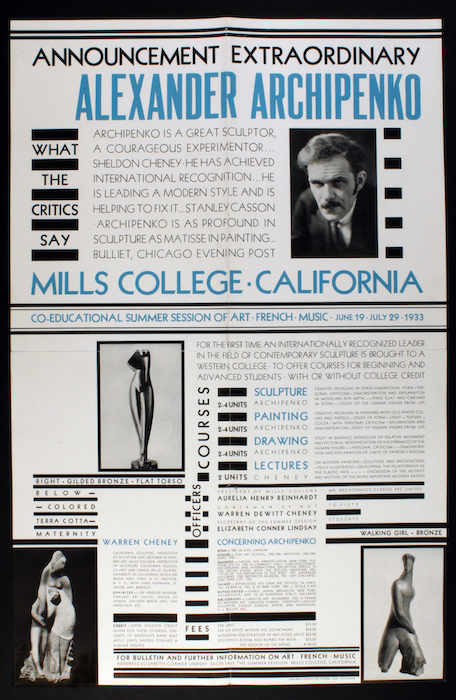

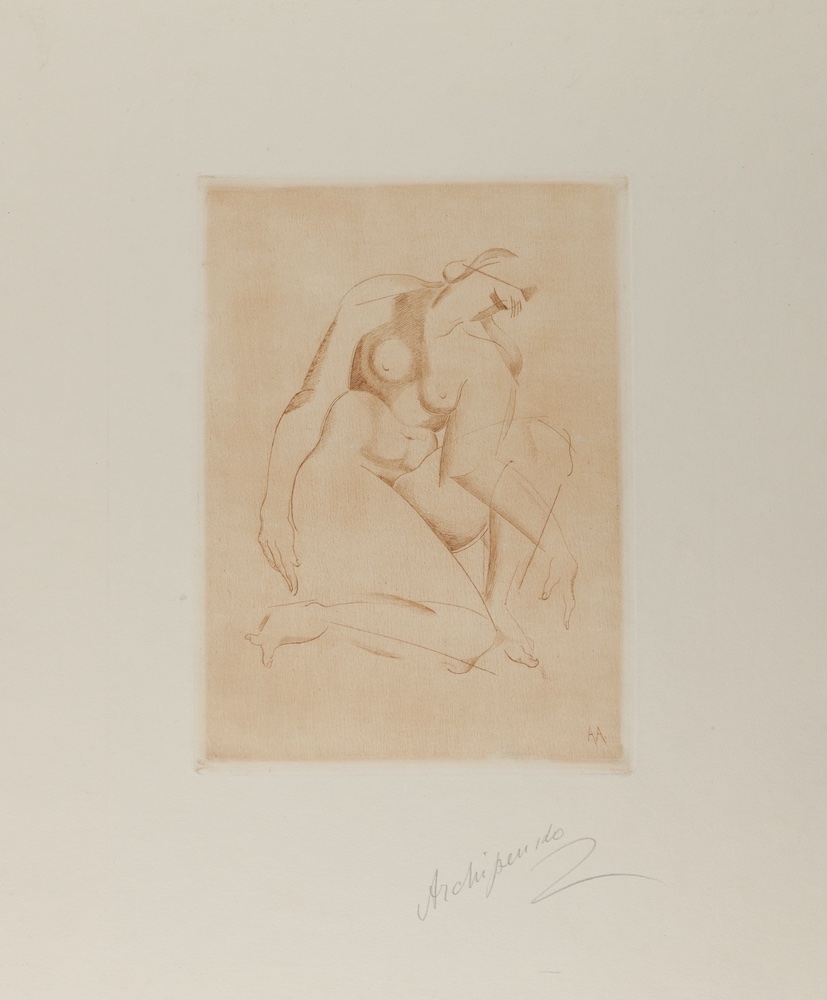

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO

In 1933 Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964) was the inaugural guest instructor for the Summer Sessions art program. At the time, he was 46 years old and already had a successful career in Europe as a Cubist sculptor. Born in Kiev, Ukraine, in his early twenties he was one of the first artists to exhibit Cubist works in Paris alongside such artists as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Marcel Duchamp.

While at Mills, Archipenko taught sculpture, painting, drawing, and design, and, although successful, Archipenko’s residency was not without some disquiet: tension appears to have arisen between Archipenko and then MCAM Director Roi Partridge around his exhibition:

During our conversation on Thursday, in which you stated you were not particularly interested in a museum exhibition of your work because museums do not sell much, I felt that you did not understand completely the present circumstances bearing upon your exhibition. In the first place, let me say I am sure the series of exhibitions of your work up and down the Pacific Coast which, at the cost of much labor, we have arranged will be of much benefit to your standing as a teacher and an artist in their part of the country. A certain amount of publicity of this sort has to be undertaken and secured before a creator can reap the economic benefits of his work, such as he may later secure through the co-operation of the dealers.

If, after such laborious and careful preparation, we were to cancel and withdraw your exhibition from the museums where it has been promised, both Mills College and yourself would lose prestige…As you may perceive, we have already been placed in some embarrassment thru [sic] the fact that you failed to send us the items originally contained in your list, but we hope this will be satisfactorily remedied in the estimation of those who receive the exhibition later.

– Roi Partridge, July 29, 19331

Archipenko would return as guest instructor the following summer, and his work was also included in a 1939 abstract art exhibition at Mills College Art Museum, during which time, Nude was acquired for the museum’s permanent collection.

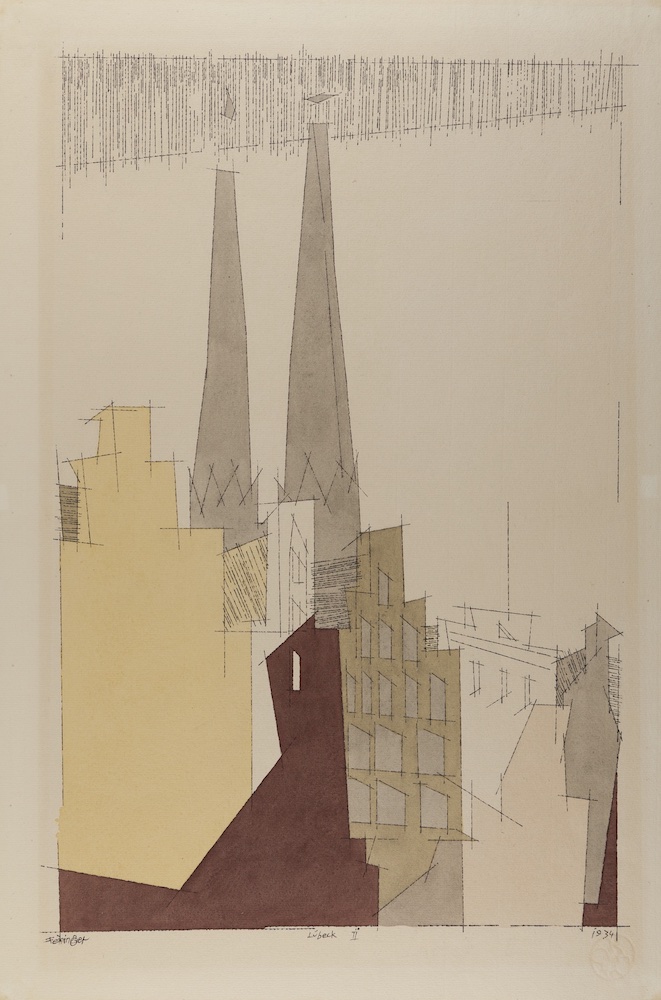

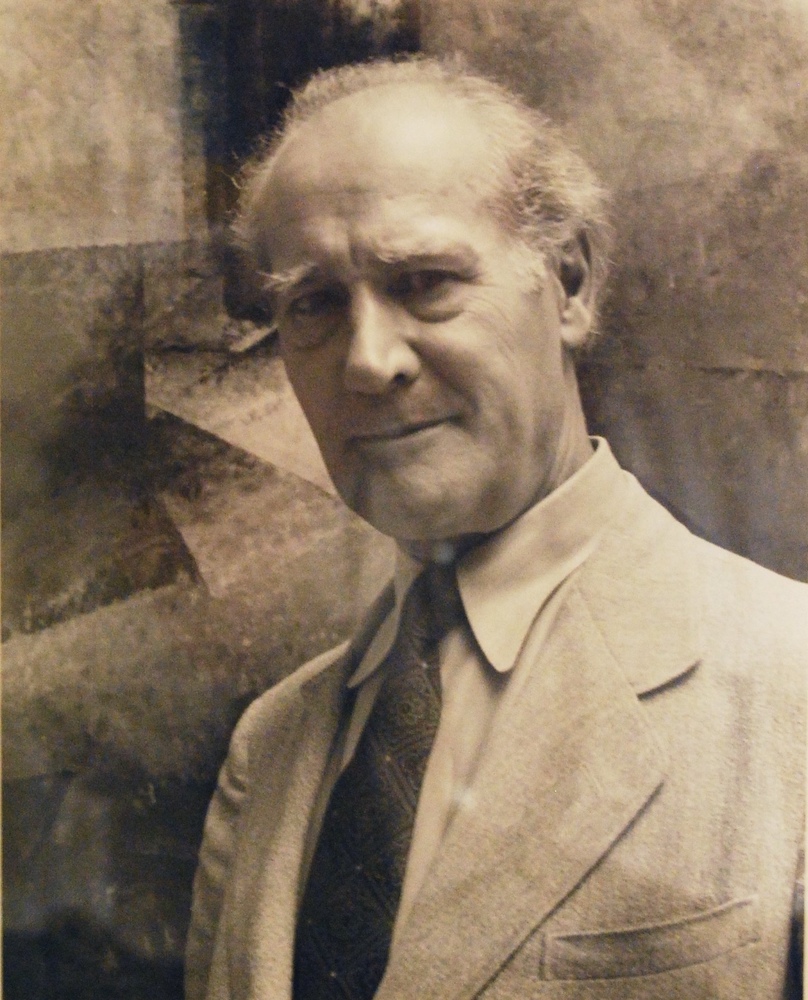

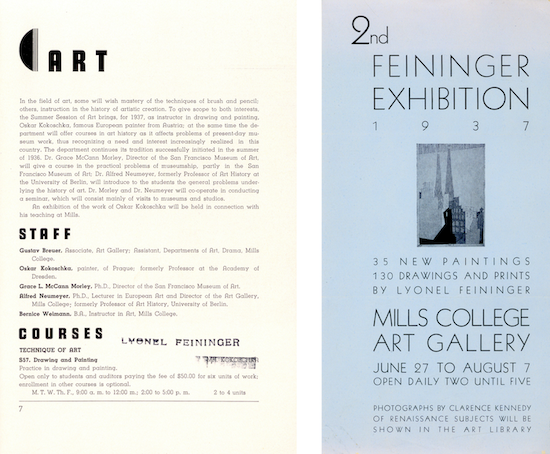

LYONEL FEININGER

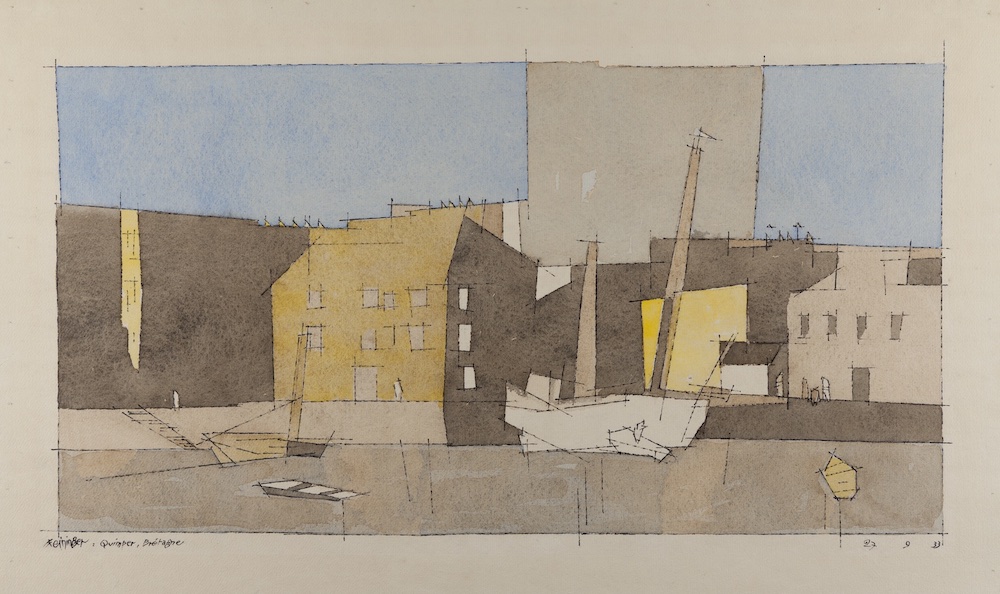

Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956) was invited to teach drawing and painting at the 1936 Summer Sessions. A German American painter, photographer, cartoonist, and teacher, Feininger was one of many artists targeted by the Nazi Party for his modernist aesthetic, believed to contribute to the moral decay of German society. The Nazis rejected abstract forms and distorted images in favor of realistic, representational paintings featuring nationalist themes. Working mostly in watercolor, ink, and graphite, Feininger’s style was noteworthy for its expressionist line quality and illustrative cartoon technique.

Feininger had been a member of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a group of artists with a shared interest in Expressionism and graphic design, which disbanded at the start of World War I; and was also a member of The Blue Rider’s successor group, Die Blaue Vier (The Blue Four). A prominent figure in the Bauhaus movement, Feininger was also one of the first teachers after the Bauhaus school’s founding in 1919.

Feininger’s 1936 Summer Sessions exhibition was not only his first solo exhibition in the United States, but also one of the earliest instances of his art ever being displayed in the country.

When I left my things in Germany, it was with the definite idea of winning my way in America without the assistance of past ‘triumphs’ obtained in another country.

— Lyonel Feininger, 19372

When the following year’s scheduled guest instructor, Oskar Kokoschka, had to cancel due to family illness, Feininger agreed to return for the 1937 Summer Sessions.

The school’s subsequent press release was positively ecstatic: “Lyonel Feininger is coming back!” states Sidney L. Gulick, Jr., “Last summer, every student working with him signed a petition asking for his return. Now you can take advantage of it. Will you be here?”3 Feininger’s return was covered widely in Bay Area newspapers and bulletins, including one feature with the amusing title, “Famous Painter Relaxes by Making Tiny Yachts.”

In a lecture given on the occasion of Feininger’s second exhibition at MCAM, Neumeyer lauded the artist’s work as the defining modern art of its time: “Surrounded by his paintings, one feels himself taken away into a land of sublime, even remote sensations.”4

LÁSZLÓ MOHOLY-NAGY

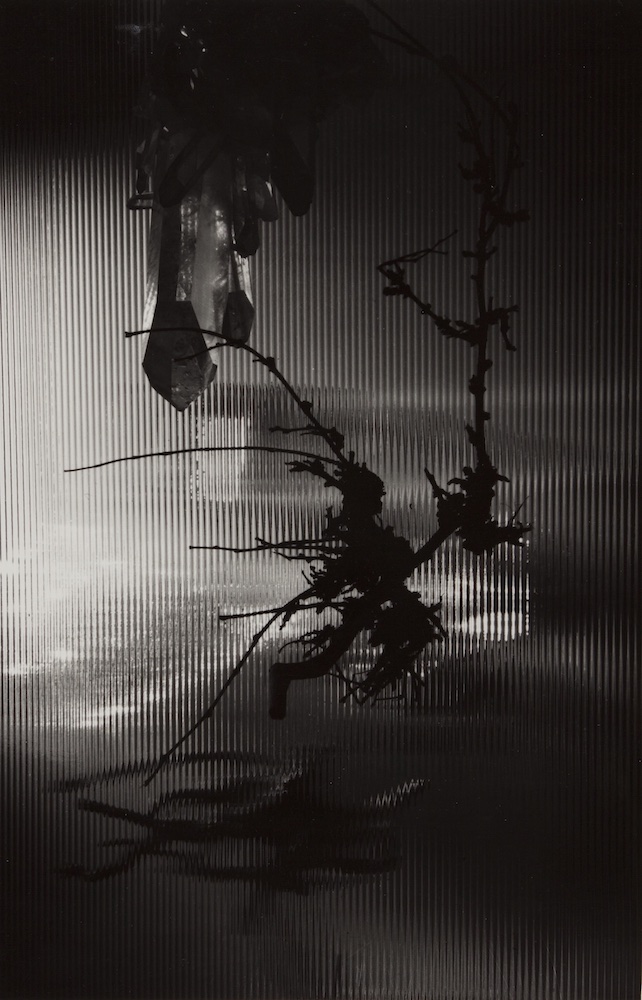

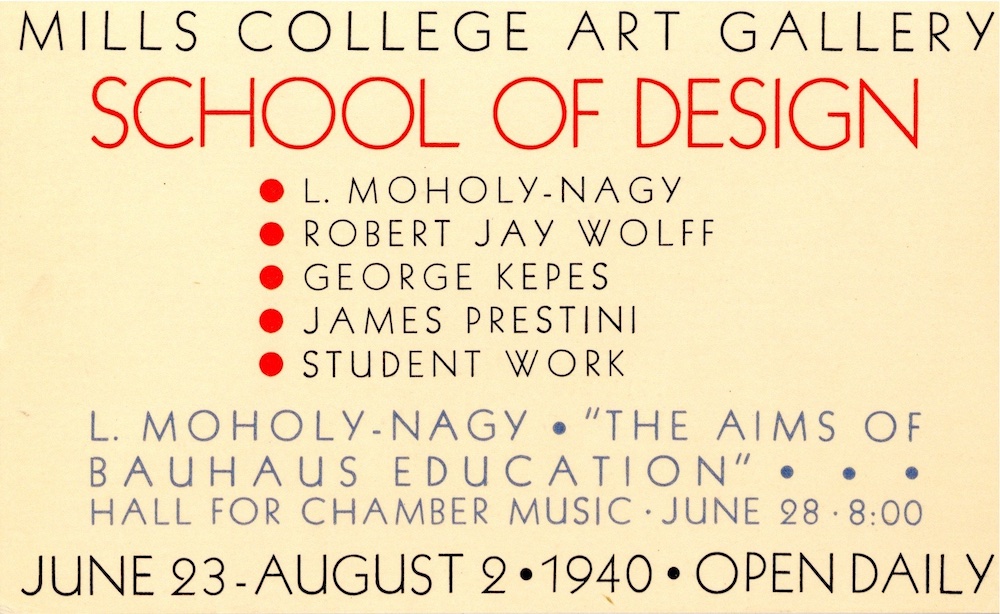

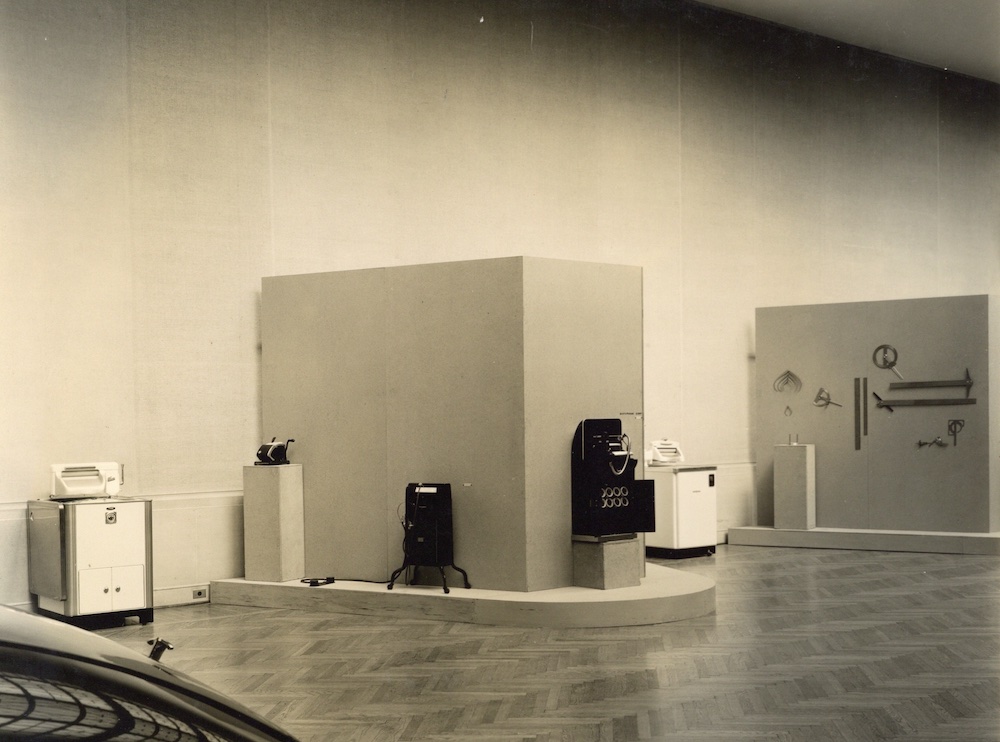

The Mills College Summer Session of 1940 concentrated primarily on the influential Bauhaus School of Design. That year’s featured guest instructor was László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), a Hungarian painter and photographer who was an integral member of the original Bauhaus school. Though influential in much of his work, Moholy-Nagy was especially instrumental in the artistic development of modern photography, graphic design and kinetic sculpture.

Initially named the New Bauhaus, the School of Design was established in Chicago in 1937 by Moholy-Nagy after the original Bauhaus in Germany was dissolved following the Nazi Party’s ascent to power and condemnation of the Bauhaus as a stronghold of communist intellectualism and Jewish influence.

Moholy-Nagy brought with him leading faculty from the School of Design in Chicago: the painter Robert Jay Wolff; the weaver Marli Ehrman; the furniture designer Charles Neidringhaus; the artist, designer, and craftsman James Prestini; and Hungarian photographer, theorist, and painter Gyorgy Kepes, who led the color workshop at the Summer Sessions.

This esteemed group taught courses in Bauhaus philosophy and crafts, including drawing, painting, photography, weaving, paper cutting, metalwork, modeling, and casting — a potent pedagogical combination of fine arts, design, and industrial knowhow that produced functional objects of stunning artistic allure.

Attendance at the 1940 Summer Sessions was among the highest in the program’s history. Moholy-Nagy’s presence was much anticipated, and a number of students enrolled in the School of Design to stay on and study with him after that summer.

The accompanying exhibition, “School of Design,” comprised Bauhaus objects, paintings, graphics, stage design, typography, graphic design, posters, and photography — the full range of work from this world leader in modernist design. Featured in the exhibition, the painting CH XI reflects a naming convention commonly used by Moholy-Nagy, utilizing letters and numbers to create titles suggestive of inventory or manufacturing codes. This convention signals his continuing interest in the pioneering Bauhaus practice of merging art and industry.

On July 18, 1940, composers John Cage and Lou Harrison presented a concert with staging and lighting by Moholy-Nagy and the artists from the Chicago School of Design. The highly successful summer sessions of 1939 to 1941 featured a series of stirring percussion-based music concerts that established Mills as a center for experimental music on the West Coast.

Moholy-Nagy’s time at Mills ended abruptly when he became ill after being bitten by a dog. He nonetheless treasured his summer at Mills; describing their experience in his biography, his wife Sibyl later wrote:

For the first time since we had left Europe, the atmosphere of a city seemed filled with an enjoyment of nonmaterial values — art, music, theatre — not as demonstrations of wealth and privilege, but as group projects of young people and of the community.5

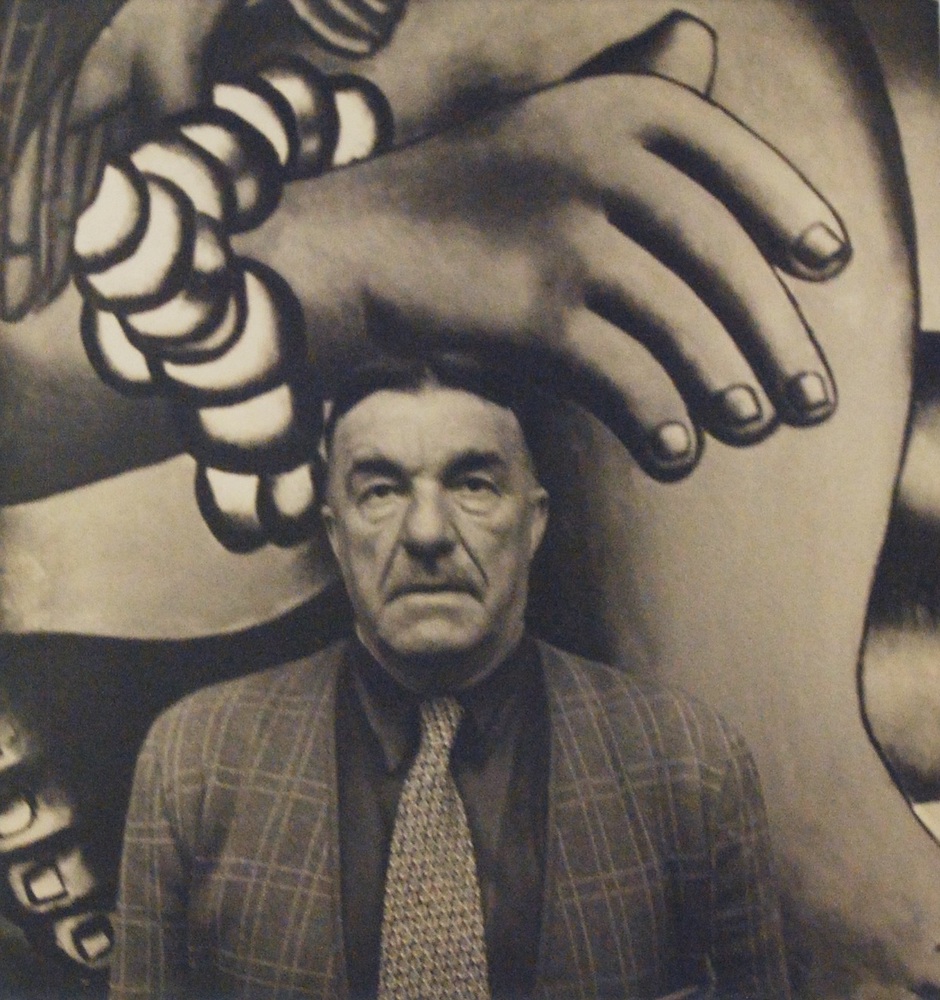

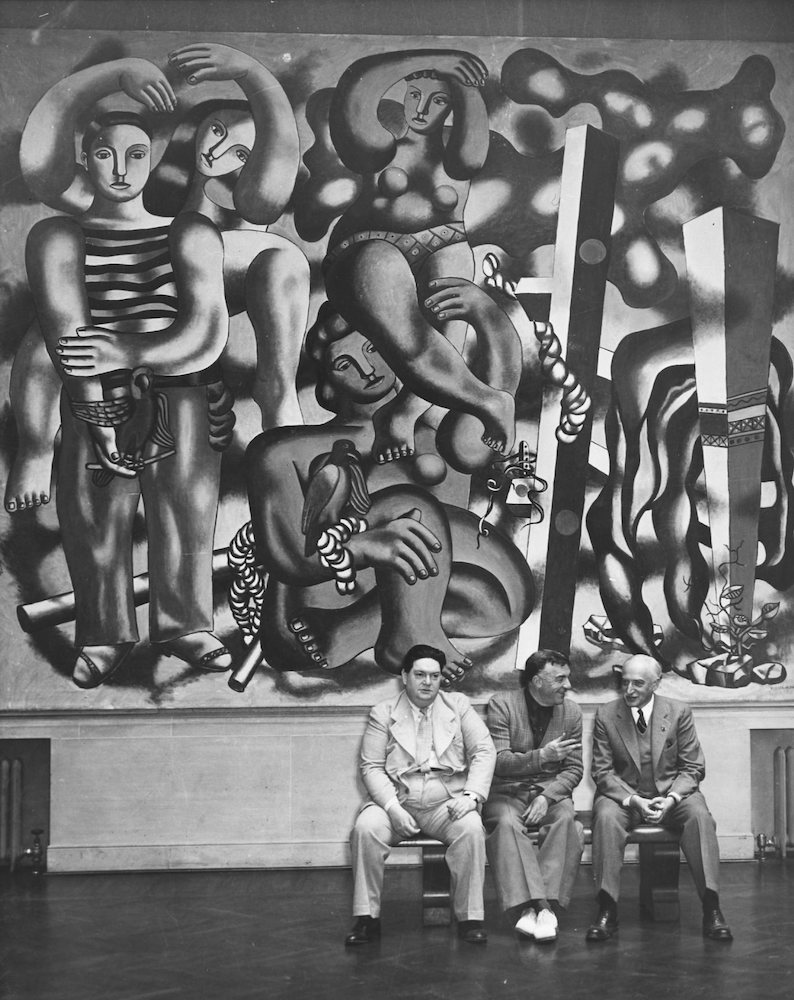

FERNAND LÉGER

Guest artist for the 1941 Summer Sessions, Fernand Léger (1881–1955) was a French painter and leading Cubist artist. As a student taking courses at the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Julian, Léger came under the influence of painting titans Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Braque. For Léger, Cubism was a means of radically transforming the relationship between the human and the mechanical into something positive and beautiful.

With the aid of an interpreter, Léger taught drawing and painting classes to the 1941 Summer Session students. A letter written to Neumeyer while he was away on vacation reported,

students were happy with Léger, for he is amiable and generous with his criticism. He sits in the little office off the painting room, drawing arms and legs, figures and faces on many sketches of his own, welcoming anyone who comes to the door with work for criticism.6

Though Léger spoke little English, he found the Mills students “magnifique.”7

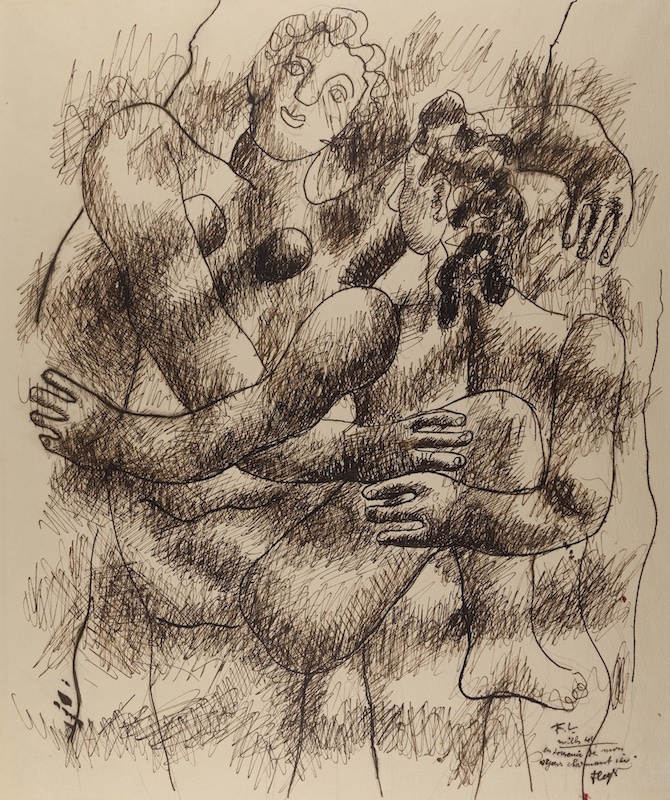

Léger’s interest in social equality and the poetry of body movement inspired his studies of acrobats, cyclists, divers, and builders. He had been working on the series Les Plongeurs (The Divers) before arriving in Oakland but gained new inspiration for his artistic kinesiology at the Mills swimming pool.

The study for The Divers, which he gifted to the Mills Art Museum in honor of his stay, powerfully captured the essence of the school’s dynamism and importance in community life and serves as permanent witness to the artistic genius such distillation demands. Léger’s Summer Sessions exhibition, which would later travel to the San Francisco Museum of Art (today, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), drew 1300 people to MCAM, the highest attendance of any exhibition that year.8

After returning to the East Coast, Léger wrote to Neumeyer expressing interest in a permanent teaching position in the U.S. Neumeyer wrote to colleagues in university art departments and art schools from Washington to Massachusetts soliciting a post for Léger: “It was one of the most rewarding experiences in my relationship with artists and their work to be in contact with this man for six weeks.”9 Unfortunately, the American academy simply was not yet ready for Léger’s genius: there were no open positions for one of this century’s greatest artists. A letter from the chairman of the art department at the University of Illinois lamenting the conservatism in academic art is typical of the responses Neumeyer received:

I think I ought to say, confidentially, that our general University Faculty and the townspeople are so conservative in their point of view in art that I am afraid a meeting point for sympathetic contacts between them and the artist would be almost impossible to establish. I dare say that this situation is not a new one to you but seems so widely prevalent among the general faculty in our colleges and universities.10

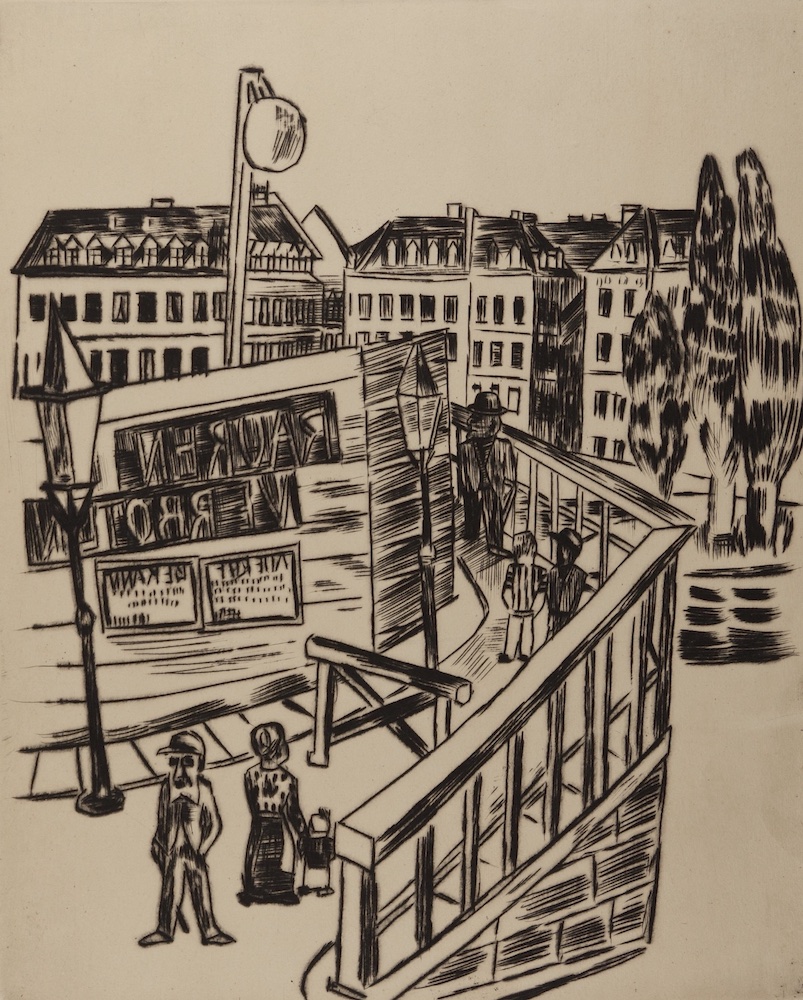

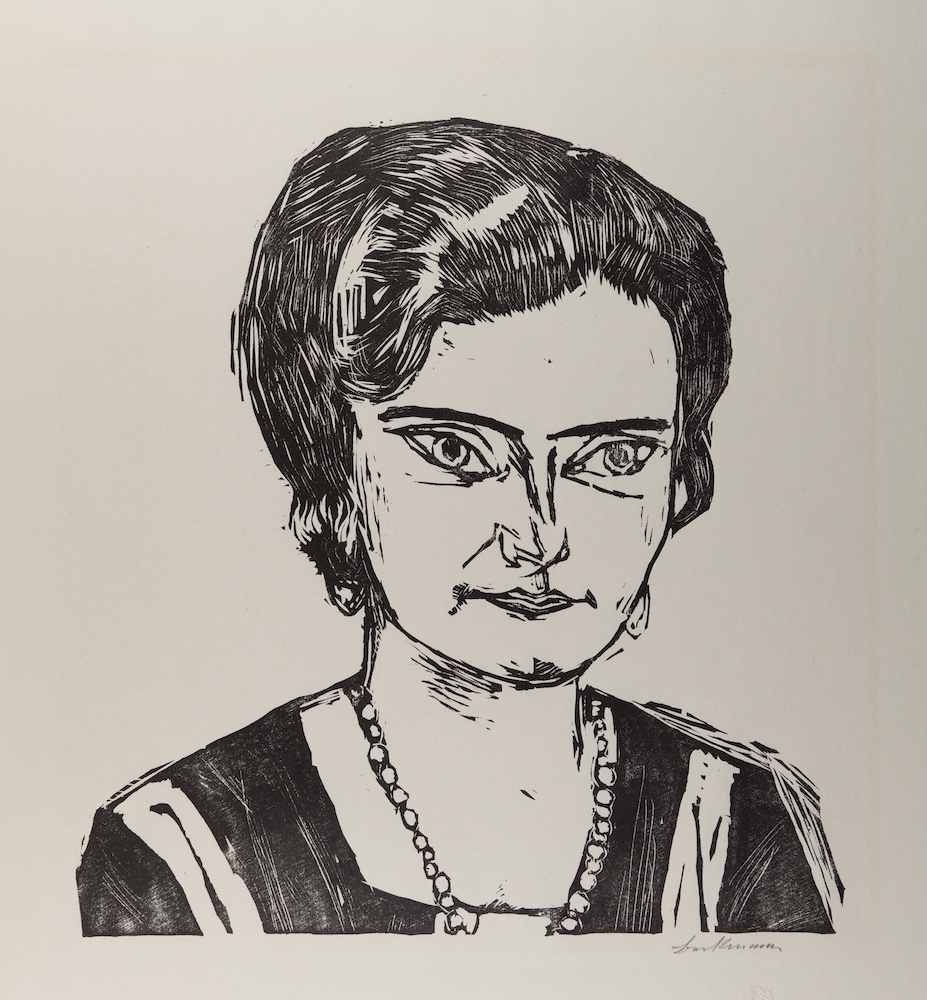

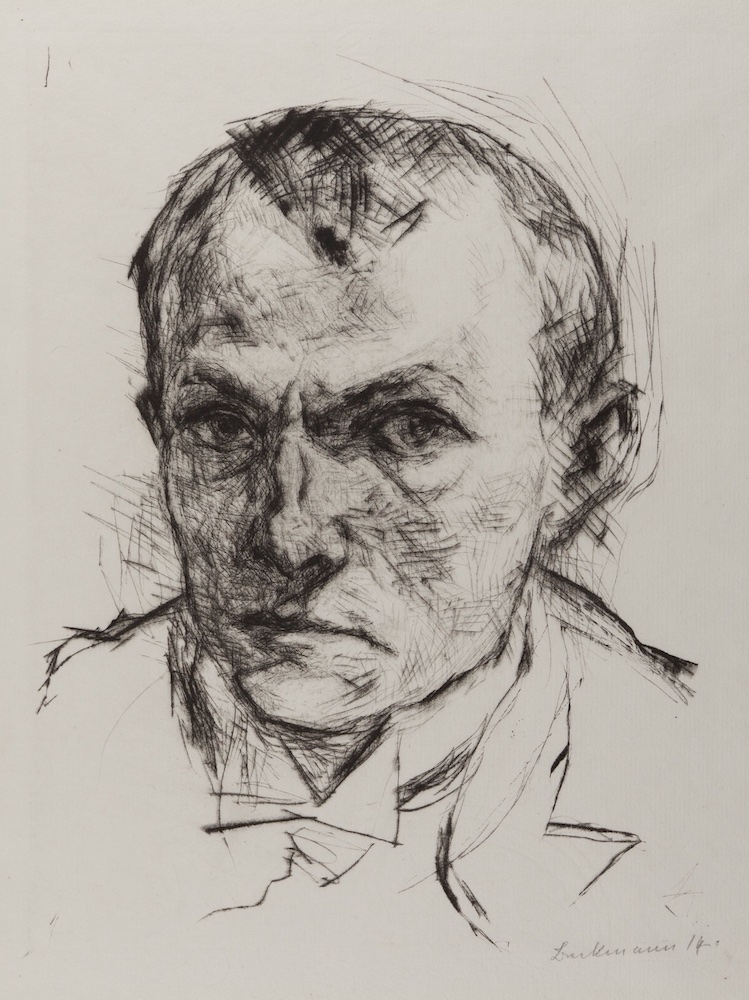

MAX BECKMANN

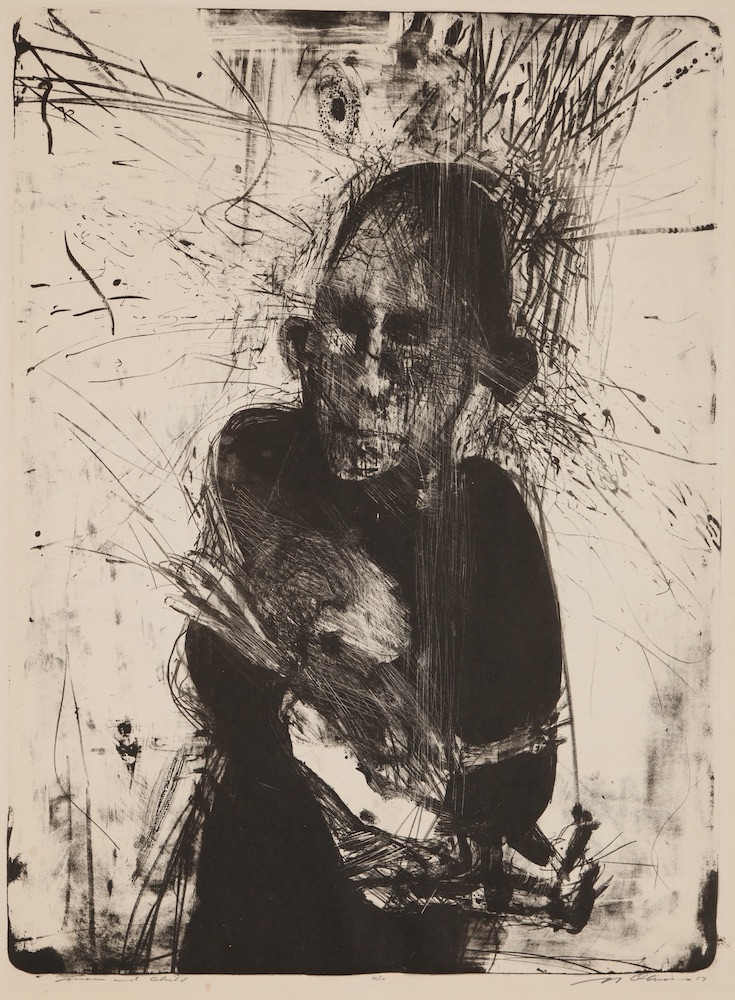

Max Beckmann (1884–1950), was a German painter widely regarded as one of the major figures of the Expressionist and New Objectivity movements. The lurid violence and suffering he witnessed as a medic in World War I were scorched into his memory and influenced his post-war oeuvre. His distorted angles, cynical self-portraits, and graphic depictions of the grotesqueries of humanity are often attributed to the trauma of his war-time experience.

One of the most renowned German artists of his time, in 1933, the Nazi government dismissed Beckmann from his teaching position at the Stadel Art School in Frankfurt, and in 1937, he and his wife fled to Amsterdam — the same year hundreds of Beckmann’s works were exhibited in ridicule in the Nazi Party’s Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition held at the House of German Art in Munich, which was designed to be the new site for German art, housing only Nazi-approved work.

Beckman was unable to secure a visa to the United States during World War II; it was not until 1947 that he and his wife emigrated to the U.S. He taught painting at the 1950 Summer Sessions, which would mark both his last teaching role as well as his last major exhibition.

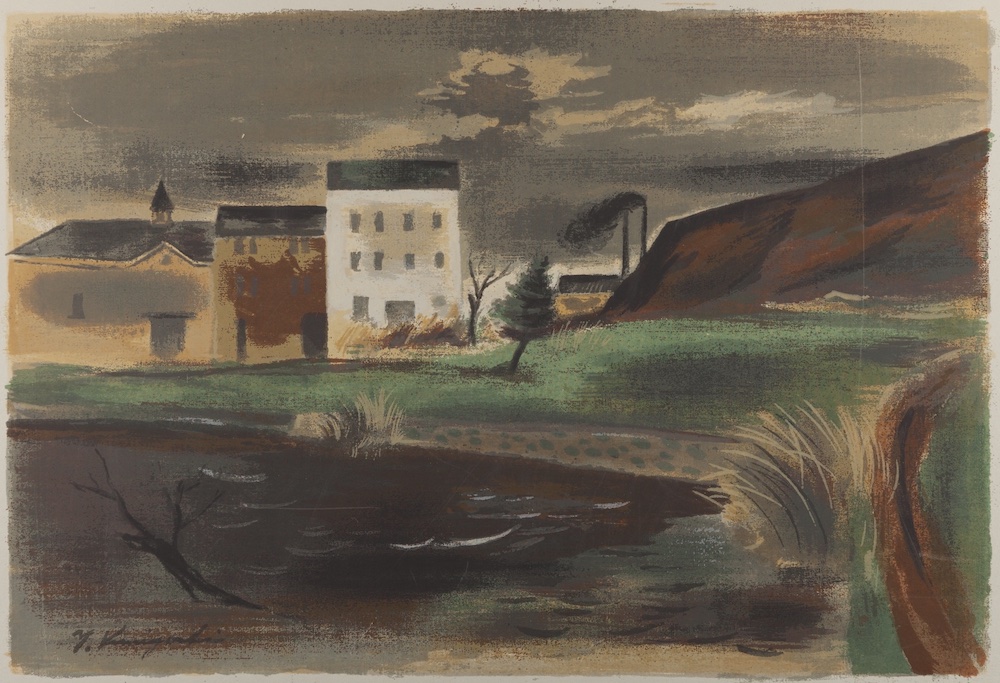

Beckmann made sketches for three paintings while at Mills: San Francisco, West-Park, and Mill in Eucalyptus Forest.11 In Mill in Eucalyptus Forest (1950), Beckmann imagines a mill nestled into the Mills College landscape, where one did not actually exist.

Summer Sessions guest instructors played significant roles in shaping subsequent generations of American artists. Nathan Oliveira (1928–2010) attended California College of the Arts and Craft (CCAC) and took Beckmann’s summer course at Mills College. He went on to become one of the most esteemed artists in the Bay Area, having developed under Beckmann expertise not only in line technique, but also in the phenomenology of being an artist-in-the-world.12

AMERICAN AND LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS

Of course, Neumeyer did not use the Summer Sessions solely for the rescue of European modernist art and artists. He also called upon some of the leading American and Latin American artists of the time to participate. In fact, his consistent success in securing leading talents for the program led San Francisco Chronicle art critic Alfred Frankenstein to praise Mills College as “providing one of the major art events of the year.”13

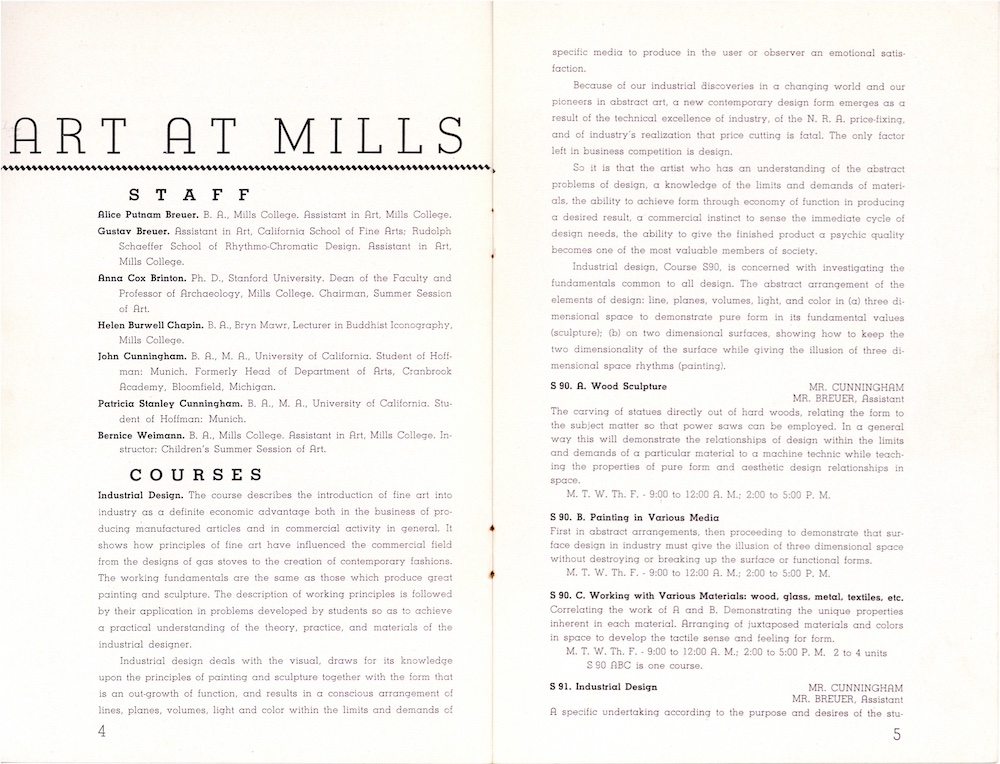

The 1935 guest instructor, California artist John Cunningham (1904–2004), was an abstract landscape artist, sculptor, and graphic designer. Originally from New York City, Cunningham attended Saint Mary’s College in Moraga, California, and earned his master’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley in 1928. There he met his wife, Patricia Stanley Cunningham, and together they studied in Germany and France. After returning to the U.S., Cunningham and his wife settled in Carmel, California where he directed the Carmel Art Institute for almost fifty years.

While at Mills College, Cunningham focused on industrial design, giving lectures with titles denoting timely relevance such as “The Trend of Art,” “Evolution of Contemporary Industrial Design,” and “Art for Industry’s Sake.” The subjects of his courses were wide-ranging and included industrial design, wood sculpture, painting, and mosaics. Cunningham’s wife Patricia accompanied him to Mills College and taught a course on fashion design.

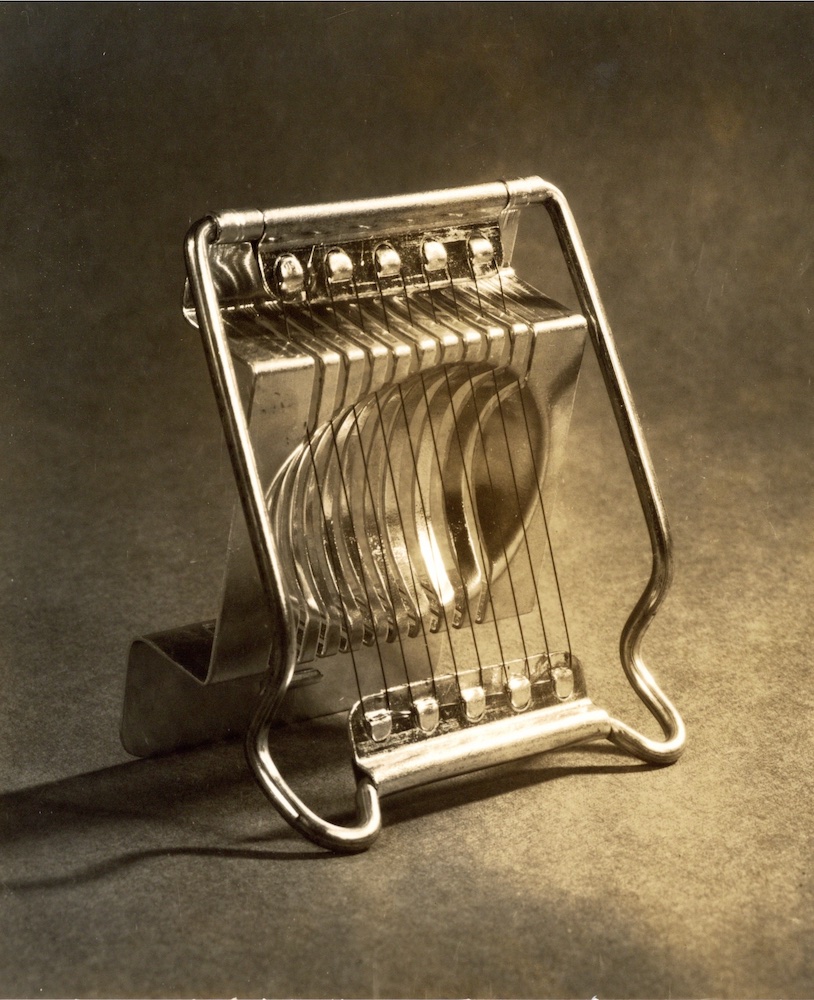

He organized the Summer Sessions exhibition, Design in Industry. Gesturing toward a pragmatic take on art, this show explored the idea of geometrical beauty expressed through machine-made, everyday objects such as ball bearings, kettles, pots and pans, and bookends.

Cunningham’s curatorial focus had been inspired by the exhibition Machine Art at the Museum of Modern Art in New York earlier that year. Cunningham borrowed pieces from this show as well as from other American designers for Design in Industry.

In 1942 and 1943, Neumeyer invited Latin American artists Antonio Sotomayor and José Perotti to teach at the Summer Sessions. Although not as well known to San Francisco audiences as Diego Rivera, Sotomayor and Perotti demonstrated an early emphasis on Latin American art at Mills College and in the Bay Area.

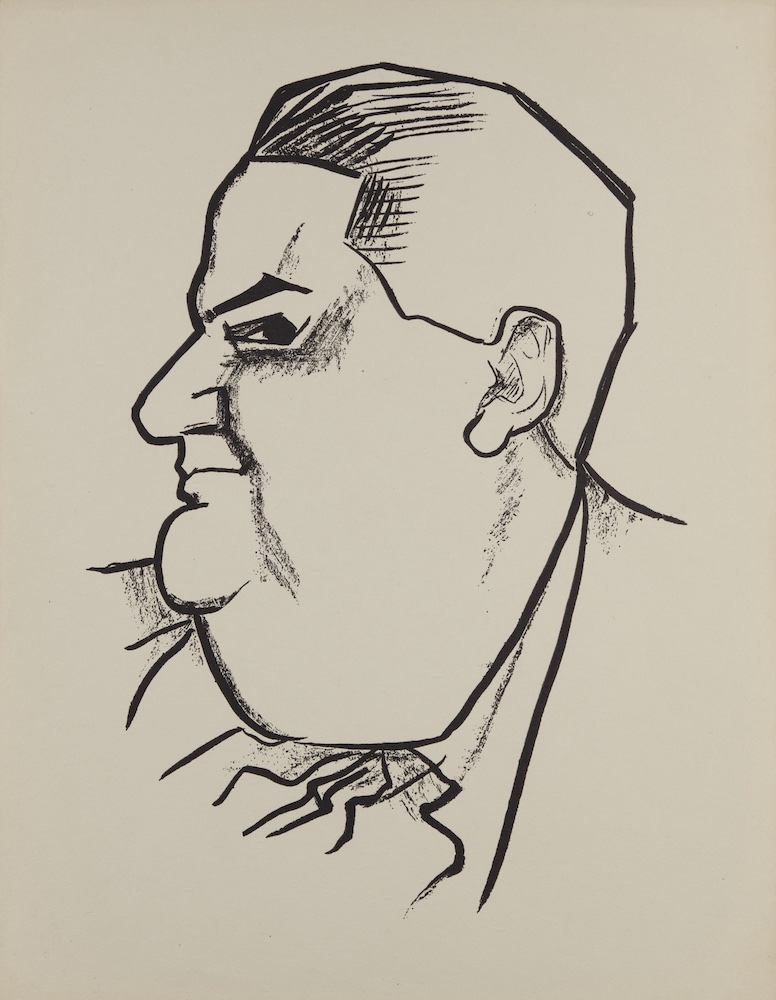

Sotomayor was born in Bolivia and moved to San Francisco in 1923 to study at the Hopkins Institute of Art. Locally, he was known for his caricatures of famous San Francisco celebrities and artists, which he exhibited in a solo exhibition in 1941 at the Renaissance Society, a contemporary arts space at the University of Chicago that also played a key role in bringing avant-garde artists to the United States.

In a review of the Latin American Art exhibition at Mills that summer, Frankenstein wrote of Sotomayor’s work:

Just why Latinos should be great caricaturists I do not know, but the three finest caricaturists who have appeared on the American art scene in my time are Miguel Covarrubias, Rosendo Gonzales, who never got as far as he should, and Antonio Sotomayor.13

French composer and Mills professor Darius Milhaud helped to establish the program’s music classes and brought guest musicians to the Summer Sessions. Some of his students went on to become famous musicians in their own right, among them Phillip Glass, Irwin Beadell, Seven Geliman, and Ben Johnston.

Sotomayor’s paintings and murals also received acclaim. By the late 1930s, a few of years after Diego Rivera arrived in San Francisco, Sotomayor, too, became a celebrated muralist for the city. He was commissioned to paint murals in the Cirque room at the Fairmont Hotel and at the Grace Cathedral in San Francisco’s Nob Hill.

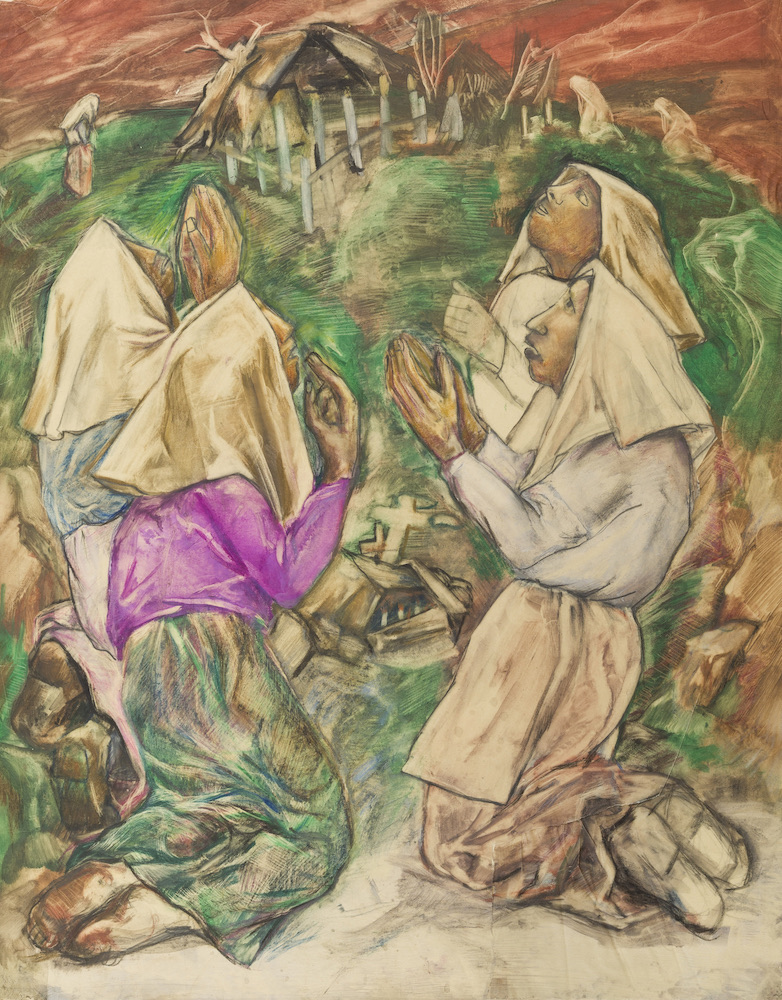

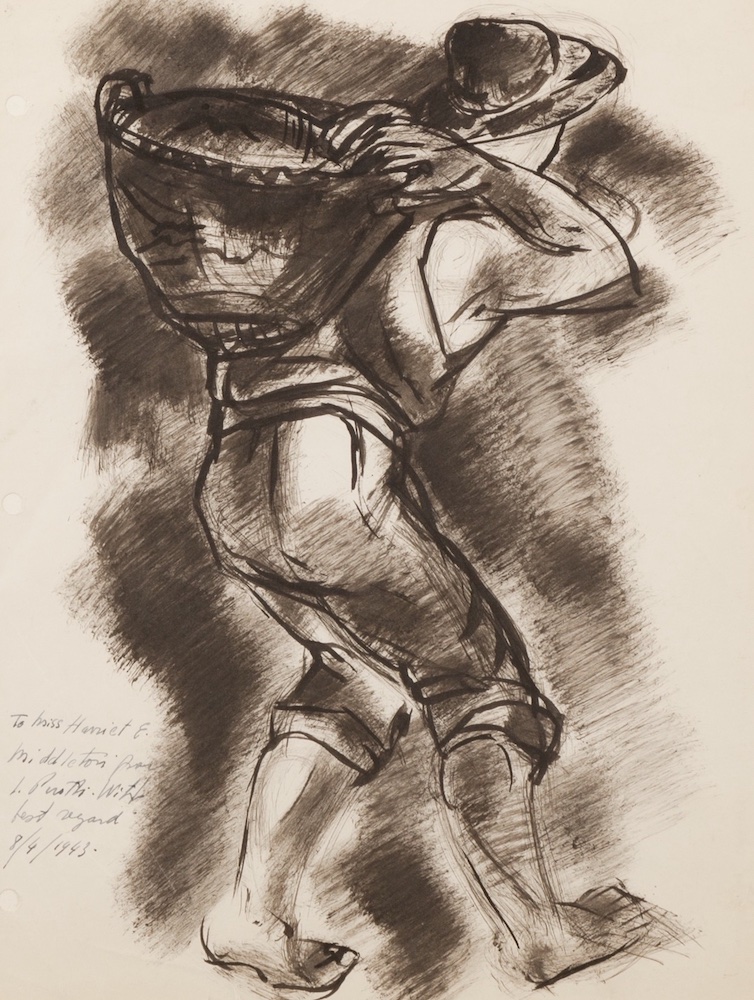

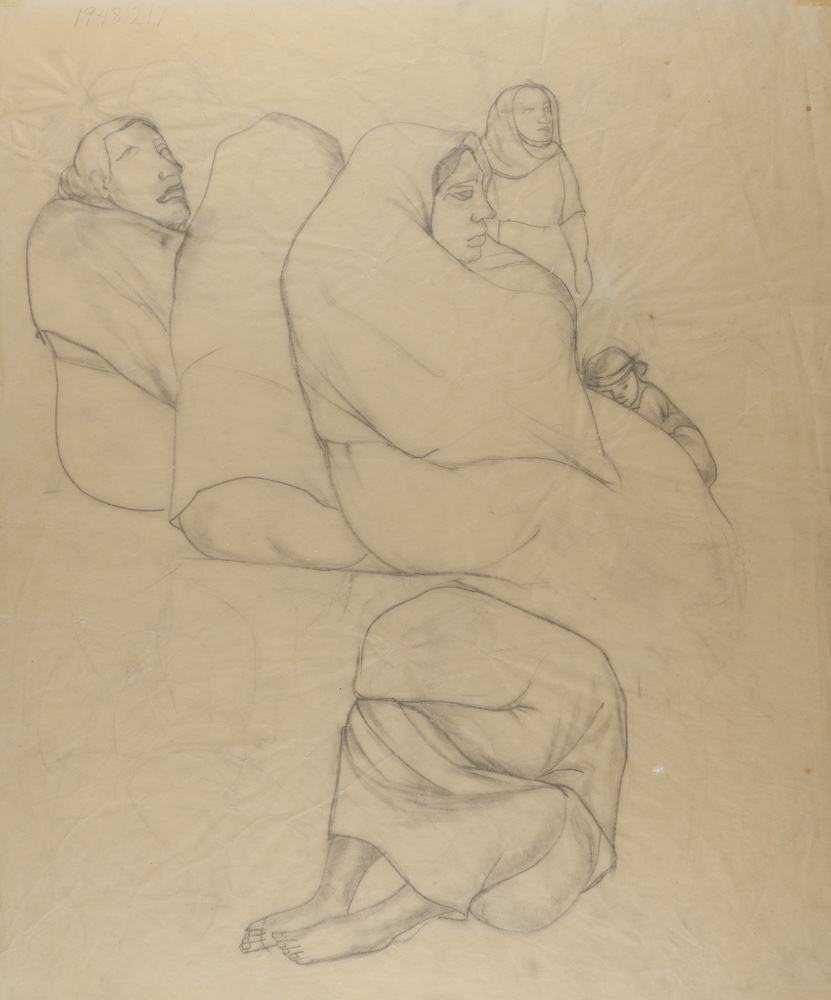

Chilean sculptor José Perotti joined Sotomayor as a Summer Sessions guest instructor in 1943.

Perotti was one of the founding members of Grupo Montparnasse, a group of Chilean artists that came together in 1922 to experiment with emerging art movements out of Paris including Cubism and Expressionism.

While at Mills College, Perotti produced the watercolor Praying Women and the ink drawing Untitled, which are now part of the the MCAM collection. He later gifted Minder’s Wives to the Art Museum, a testament to a meaningful experience teaching at Mills College.

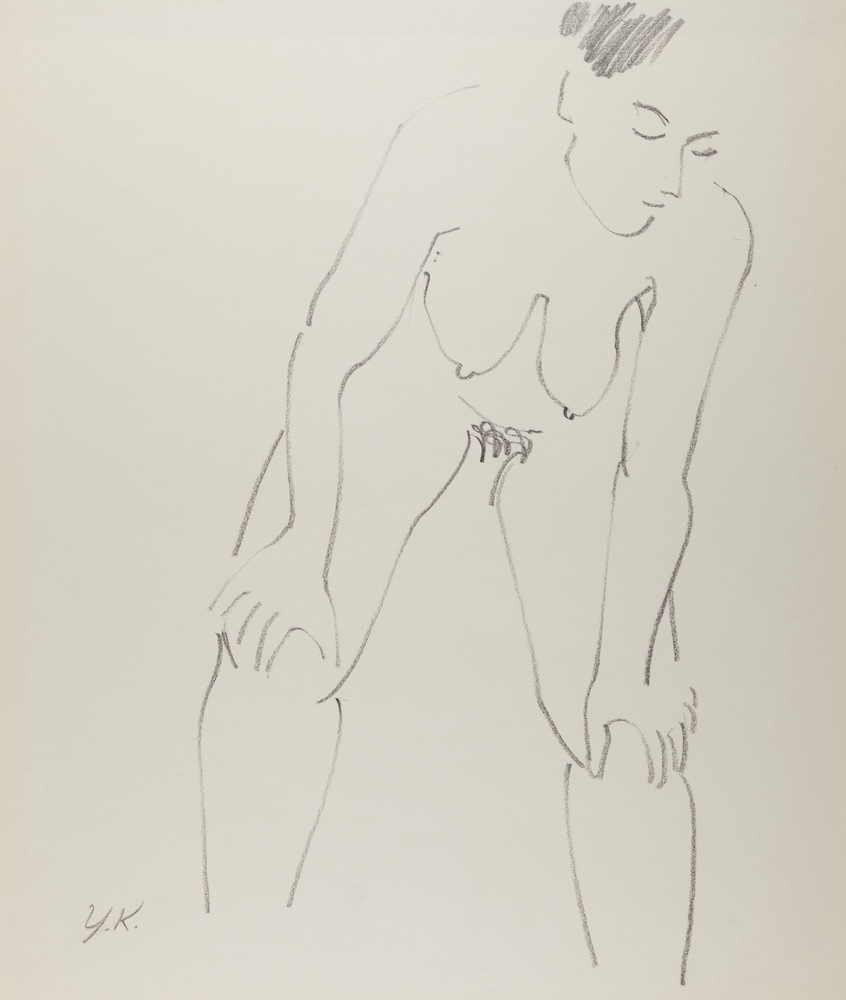

The 1949 Summer Sessions featured Yasuo Kuniyoshi (国吉 康雄) (1889–1953), an eminent Japanese American painter, photographer, and printmaker best known for his images of common objects and figurative subjects like female circus performers and nudes.

After the U.S. entered WWII, Kuniyoshi lived under the pall cast by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s policy branding Japanese Americans the “alien enemy.” This disgraceful moment in American history, enshrined as Executive Order 9066, authorized the forced removal of Japanese Americans to concentration camps. However, as a resident of New York state at the time, Kuniyoshi was able to avoid imprisonment. In 1948, one year before Kuniyoshi came to Mills College, he became the first living artist to be awarded a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Ingenmyoo (Little Pond) was a gift to the Mills College Art Museum from its founder, Mills College Trustee Albert M. Bender, in 1943, six years before Kuniyoshi taught at the Summer Sessions.

Additional artists to guest instruct the Summer Sessions included Leon Kroll (1938), Frederic Taubes (1939), Dong Kingman (1944, 1952), Robert Boardman Howard (1945), Reginald Marsh (1946), Clarence W. Merrit (1947), Felix Emanuele Ruvolo (1948), and Fletcher Martin (1951).

The Mills College Art Museum’s leadership in the Summer Sessions calls attention to the important political, social, and cultural work done by émigré artists in their roles as teachers, change agents, and sources of inspiration. It also makes an indelible statement on the power of academic institutions and museums to play a formidable role in charting history, reflecting the present, and shaping the future. The program and its artists operated within the larger context of the Bay Area’s vibrant visual arts community during the 1930s through 1950s and became a vital part of the local creative community. Neumeyer’s considerable contributions to the Summer Sessions were matched by other émigré faculty who helped establish Mills as a crucible for artistic genre- and era-defining innovation and experimentation.

NOTES

-

Letter from Roi Partridge to Alexander Archipenko, July 29, 1933, Mills College Art Museum Archive. ↩︎

-

Letter from Lyonel Feininger to Alfred Neumeyer, 1937, Mills College Art Museum Archive. ↩︎

-

Sidney L. Gulick, Jr., Letter to Mills College, June 2, 1937, Mills College Art Museum Archive. ↩︎

-

Dr. Alfred Neumeyer, “The Art of Lyonel Feininger,” Lecture transcript, July 18, 1937, Mills College Art Museum Archive. ↩︎

-

Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Moholy-Nagy: Experiment in Totality (Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1969) ↩︎

-

Letter to Alfred Neumeyer, Museum Archives in the Special Collections, F.W. Olin Library, Northeastern University, July 22, 1941. ↩︎

-

Visiting Artists at Mills, Mills College Art Museum Archive ↩︎

-

Annual Report May 1941-42, Museum Archives in the Special Collections, F.W. Olin Library, Northeastern University. ↩︎

-

Letter from Alfred Neumeyer to James Grote Van Derpool, October 30, 1941, Mills College Art Museum Archive ↩︎

-

Letter from James Grote Van Derpool to Alfred Neumeyer, November 5, 1941, Mills College Art Museum Archive ↩︎

-

Peter Selz, “The Impact from Abroad: Foreign Guests and Visitors,” On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900-1950, ed. Paul J. Karlstrom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 97-118. ↩︎

-

Thomas H. Garver and George W. Neubert, Nathan Oliveira: A Solo Exhibition 1957-1983 (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1984). ↩︎

-

Alfred Frankenstein, “From Bolivia – Via the Palace Hotel,” San Francisco Chronicle (1942) ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎