Since its founding in 1925, the Mills College Art Museum collection has grown to include over 12,000 objects. These works are frequently loaned to other museums for exhibitions, appear regularly in high-impact publications, and are made accessible, both in-person and digitally, to scholars, curators, faculty, and students for independent research. In the past five years alone, numerous works from the collection have found pride of place in exhibitions across the country; for example, this series of ceramic pieces by Mary Tuthill Lindheim that appeared in the Crocker Art Museum’s exhibition Mary Tuthill Lindheim: Kindred Responses to Life (2024-2025) in Sacramento, California.

Diego Rivera’s early work, Mother and Child, traveled with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art exhibition, Diego Rivera’s America (2022-2023), along with a portrait of the artist taken by the influential Bay Area photographer Edward Weston.

An early figurative sculpture by Adaline Kent, one of midcentury America’s most innovative artists, appeared in Adaline Kent: The Click of Authenticity (2022) at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno; and Miriam Schapiro’s Nine Patch Gold crossed the Bay for the San Francisco Center for the Art of the Book’s Possibilities: When Artist Books Were Young (2022).

Black and White Suckers by Wayne Thiebaud was loaned to the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art in Davis, California, for Wayne Thiebaud Influencer, A New Generation (2021); and Hero by Phillip Lindsay Mason was included the de Young Museum’s presentation of Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, 1963-1983 (2020) in San Francisco.

While a wide variety of artworks from the MCAM collection are researched, written about, and loaned out every year, there are certain works that prove more popular than others; here are the top five.

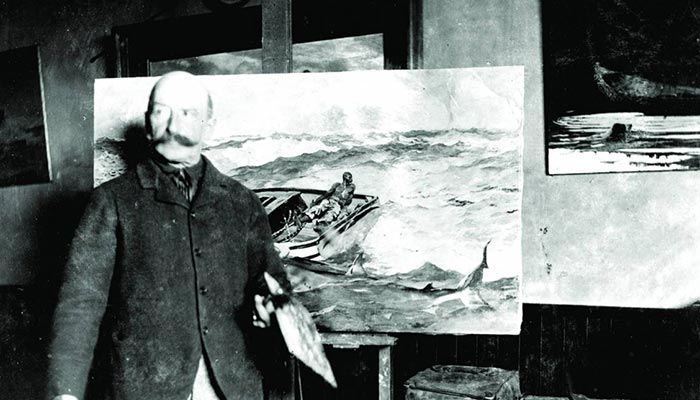

Waiting for Dad (Longing), 1873, by Winslow Homer

Winslow Homer’s watercolor, Waiting for Dad (Longing) is the Art Museum’s most loaned and studied work.

Winslow Homer (1836–1910) was an American landscape painter and illustrator, best known for his marine subjects. He is considered one of the most important painters of 19th-century America and a preeminent figure in American art. Largely self-taught—his mother was a gifted watercolor painter and his first teacher—Homer launched his artistic career working as a commercial illustrator. He subsequently took up oil painting and worked extensively in watercolor, amassing a groundbreaking and prodigious oeuvre. Through his work, Homer chronicled some of the most turbulent and transformative decades in American history, creating iconic paintings that, for example, illuminated the devastating effects of the Civil War on landscapes and in the lives of formerly enslaved people and soldiers. Turning to emotionally charged depictions of the dramas of heroism, life in rural settings, and life at sea, Homer’s work grappled with mortality and the ambiguous relationship between humans and the natural world.

Waiting for Dad (Longing) was donated to Mills College in 1912 by Jane Tolman, the sister of Susan Mills, co-founder of Mills College with her husband Cyrus Mills. Tolman was an art historian at Mills who developed a pioneering art history curriculum in 1875 that was unique in California and remarkably far reaching and forward-thinking for its time.

Homer painted Waiting for Dad (Longing) in Gloucester, Massachusetts during one of his working vacations; it was there that he first seriously dedicated himself to watercolors. During his stay in Gloucester, a catastrophic ocean gale swept up the Atlantic and pummeled the town. Waiting for Dad (Longing) was Homer’s memorial to the fishermen who were lost at sea and the families they left behind.1

The work’s title allows us to share the thoughts of the boy whose face is turned away from us. An open-ended narrative is created as the boy looks off to the horizon; there is a sense of anxiety and uncertainty about whether his father will ever return. Hope and fear are made to serve as the emotional undercurrents that swirl just beneath the calm, glassy ocean surface, inscribing this work with deeper resonance, a sense of longing.

Waiting for Dad (Longing) has been loaned to numerous museums for exhibition including Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents (2022), organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; Homer at the Beach: A Marine Painter’s Journey, 1869-1880 (2019), organized by the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester, Massachusetts; Winslow Homer and the Critics: Forging a National Art in the 1870s (2001), organized by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri; and Winslow Homer in Gloucester (1990), organized by the Terra Museum of American Art in Evanston, Illinois. It has also been featured in the monographs The Watercolors of Winslow Homer (2001) by Miles Unger; and William Cross’ Winslow Homer: American Passage (2022).

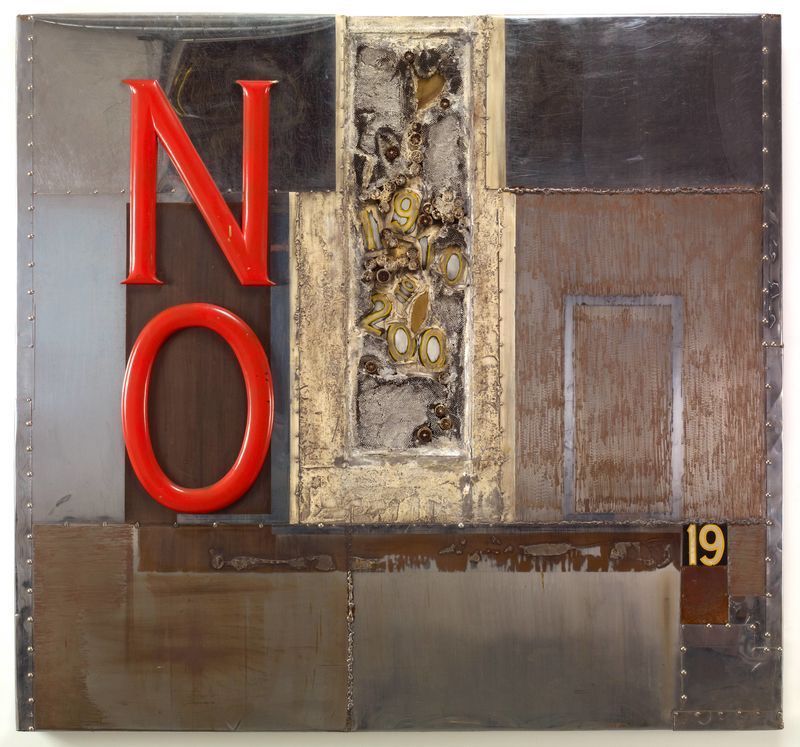

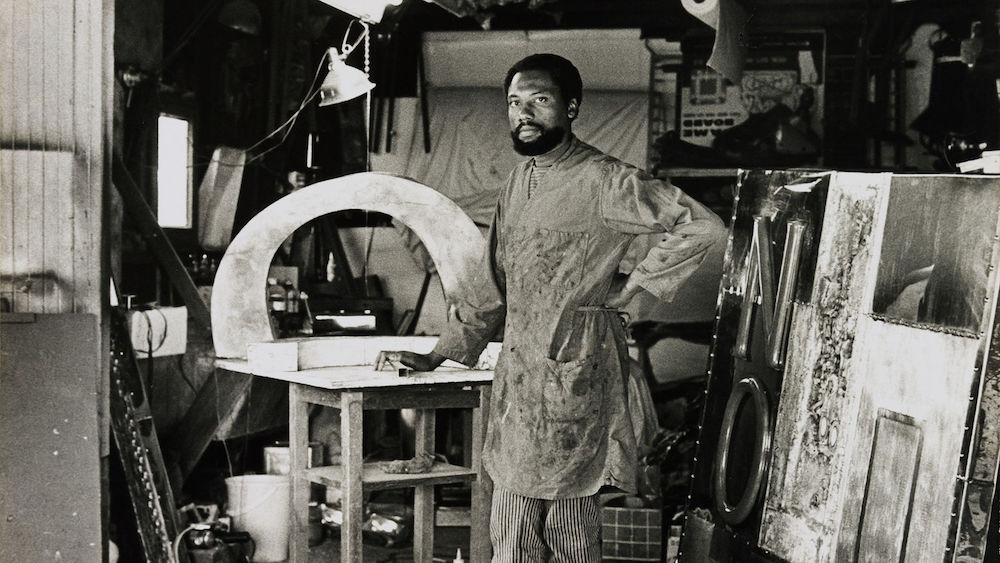

No Time for Jivin’ (Containment Series), 1969, by John Wilfred Outterbridge

Artist John Outterbridge (1933–2020) was a pioneering California assemblagist, activist, and educator who scavenged scrapyards for materials to create a new visual language for expressing the complexities of Black experiences in America. A key figure of the California Assemblage movement in the 1960s and the director of the Watts Towers Art Center from 1975 to 1992, Outterbridge became a driving force for a Los Angeles community of African American artists that included David Hammons, Noah Purifoy, John T. Riddle Jr., and Betye Saar.

Themes based on Outterbridge’s personal life figure prominently in his work. Born in segregated North Carolina in 1933, Outterbridge’s interest in salvaged materials began with his father, a hauler and mover who made a living by recycling metal and machine parts. The family’s backyard was a playground of discarded furniture, scrap metal, and old appliances. A childhood playing with the leftovers of modernity led Outterbridge to develop an appreciation for both the practical and artistic dimensions of using found objects in his art.

I had a mother and a father who had a lot of faith in cast-offs, the beauty and the aesthetics of what is not of use anymore, and that has always excited me because I saw old fences, degraded buildings, and scrub rags not as foreign objects but as being of a piece in the language of life, each with a lot of kinship between them.2

No Time for Jivin’ is part of Outterbridge’s Containment Series, which grew out of an interest in how boundaries are constituted, as well as a desire to break through the societal and institutional mechanisms that reify them. The artworks in the series were created with the detritus from the 1965 Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles, which saw six long days of protest against racialized living conditions, limited employment opportunities, and the racist and abusive practices of the Los Angeles Police Department.

In the work, metal sheets welded together become the canvas for a composition of brass address numbers, steel mesh, shotgun casings, and bright red letters from a fallen shop sign spelling out the word “NO”—materials that are at once vehicles of their own stories, objects of contemplation, and indicia of meaning outside themselves. No Time for Jivin’ was made in 1969 and emblematized the final year of a tumultuous decade that saw radical upheaval and change: pivotal moments of the Civil Rights Movement, vehement anti-war protests, and profound social change.

No Time for Jivin’ has been loaned for domestic and international traveling exhibitions including Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (2017), organized by the Tate Modern in London and shown at the de Young Museum in 2019; Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties (2014), organized by the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York; Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980 (2011), organized by the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, California; and Unthinkable Tenderness: The Art of Human Rights (1998), organized by the San Francisco State University Art Gallery. It is on loan once again for the Whitney Museum’s Sixties Surreal opening in August 2025 in New York.

CH XI (39), 1939, by László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) was a Hungarian painter and photographer who was an integral member of the Bauhaus school in Germany, which sought to unite fine art and design, creating useful and beautiful objects and architecture suited to everyday modern life.

Moholy-Nagy was forceful advocate for the integration of technology and industry into the arts, and believed that, instead of making paintings for a privileged few, art had to become egalitarian, scientific, and technologically advanced in order to prime the viewer for actively engaging with the rapidly changing modern world.

From 1923 to 1928 he was the founder and director of the photography department of the Bauhaus school in Germany, which closed after being targeted by the Nazi regime as a center of communist intellectualism and Jewish influence. In 1935, Moholy-Nagy fled Germany, settling in Chicago in 1937 and founding the School of Design, which survives today as part of the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Though influential in much of his work, Moholy-Nagy was especially instrumental in the artistic development of modern photography, graphic design, and kinetic sculpture, and he encouraged artists to swap their brushes, pigments, and canvases for cameras, televisions, and searchlights. He would later, however, return to painting at a time of unprecedented economic, political, and moral crisis: the 1930s and 40s, an era marked by the devastating fallout of the Great Depression and the Second World War.

In 1940, Moholy-Nagy was invited by then MCAM director Alfred Neumeyer to be a featured guest instructor for the Mills College Summer Sessions. The Summer Sessions was an annual series of co-educational classes and workshops open to students and the public that ran from 1933-1952, and that hosted an eclectic mix of renowned European, American, and Latin American artists to teach, exhibit, and celebrate their groundbreaking work. At the end of that summer, the Art Museum purchased CH XI (39) for the permanent collection.

CH XI (39) demonstrates Moholy-Nagy’s use of techniques and forms he explored in other media. He borrows from the serpentine shapes of his wire and glass-filled sculptures, attempting to generate the illusory effect of light and the interplay of transparent and translucent forms. Instead of directly mimicking the industrial world, his vibrant tube forms in this later work take up looser, more organic curves with their outer surfaces textured and tooled by hand. Although CH XI (39) uses the most conventional of materials, oil and canvas, he inscribes directly onto the painted surface of his canvas, employing a technique he developed for his paintings on plastic. Reflecting the Bauhaus conception of melding art and industry, CH XI (39) follows a naming convention often employed by Moholy-Nagy, in which letters and numbers are used together to create titles that mimic industrial inventory or manufacturing codes. The interplay between art and industry, and its impact on humans, is a motif frequently taken up by Moholy-Nagy in his work.

Numerous scholars have written about CH XI (39), and the work itself was included in the exhibition The Paintings of Moholy-Nagy: The Shape of Things to Come (2015) organized by the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

Magnolia Blossom and Magnolia Blossom, Tower of Jewels, 1925, by Imogen Cunningham

Imogen Cunningham was a prolific American photographer known for her botanical photography, nudes, and industrial landscapes. During the 1920s and 1930s, Cunningham served as the Mills College campus photographer and was married to Roi Partridge, the first director of the Mills College Art Museum.

Magnolia Blossom and Magnolia Blossom, Tower of Jewels are perhaps Cunningham’s most well-known botanical images; both have been written about extensively and can be found in museum collections around the world.

In each image, the closely cropped flower fills the entire frame and is tilted toward the viewer like a presentation piece. Cunningham resists making the whole plant her subject and instead draws the viewer’s gaze inwards toward the innermost folds and stamen of the blooming magnolia flower. The pistils and stamens are in sharp focus, and the petals become a dazzling study of light, shadow, and translucence, with each petal yielding the secrets of its delicate surfaces and textures. The net effect allows viewers to see a familiar subject in a new way. It is a stirring and also decidedly unsentimental approach to a familiar and too-often romanticized subject matter.

This groundbreaking technique was at the heart of a new form of modernist photography ushered in by the artists of Group f/64 of which Cunninghame was a member, along with Ansel Adams, John Paul Edwards, Alma Lavenson, Sonya Noskowiak, Brett Weston, and Edward Weston. This collective of early 20th-century Bay Area photographers shared a modernist photographic style characterized by sharp-focused and closely cropped images of simple subjects. Their name, f/64, was taken from the smallest lens aperture on their large format cameras, which allowed them to capture the greatest possible depth of field to create sharply detailed prints. Group f/64 believed that the camera was a direct window to the real world, and that the highest aim of photography was to capture the “pure” subject by presenting reality clearly and in an orderly fashion. Both Magnolia Blossom and Magnolia Blossom, Tower of Jewels exemplify this forward-thinking style.

Cunningham’s experimentations in her own garden were in the vanguard of this aesthetic shift. Her famous botanical prints, it should be noted, were the result of the real-world constraints on her ability to be out in the world in search of inspiration. As the mother of three young children, her life was largely circumscribed by the boundaries of the family’s Oakland home: “The reason I really turned to plants was because I couldn’t get out of my own backyard when my children were small.”3 By the end of the 1920s, Cunningham was one of the most sophisticated and experimental photographers at work on the West Coast, contributing significantly to the recognition of photography as a fine art.

Magnolia Blossom, Tower of Jewels, was a gift from Mills College alumna Alice Hardwood. As a member of the Class of 1924, Hardwood would have been a student at Mills while Cunningham served as the campus photographer. I like to imagine that Hardwood knew Cunningham and may have even had her picture taken by the artist or purchased her work at the Mills College shop where Cunningham would occasionally sell her photographs.4

NOTES

-

William Cross, Winslow Homer: American Passage (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022), 173. ↩︎

-

Aliese Thomson Baker, “John Outterbridge,” Artforum, September 12, 2011,

https://www.artforum.com/columns/john-outterbridge-discusses-his-show-at-laxart-198290/ ↩︎ -

Imogen Cunningham and Edna Tartaul Daniel, Imogen Cunningham: Portraits, Ideas, and Design (Berkeley: University of California Regional Cultural History Project, 1961), 26. ↩︎

-

Judy Dater, Imogen Cunninghame: A Portrait, (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1979), 14. ↩︎