Diego Rivera’s 1926 painting Mother and Child is one of the important gems in the Mills College Art Museum’s collection and reflects the museum’s early and deep engagement with Mexican and Latin American modernist artists.

Through the generosity of Oakland businessman A.S. Lavenson and the museum’s founder Albert Bender, MCAM was the second museum in the United States to acquire Rivera’s work. Lavenson’s daughter, Alma, was an aspiring photographer and Bender was instrumental in introducing her to San Francisco’s burgeoning photographic community. He also encouraged her to meet and purchase work by Rivera when she traveled to Mexico in 1926.

Lavenson’s letters from Mexico City to her father paint a colorful picture of her quest to acquire a work for the museum:

At last we have actually met Rivera. We called upon him early this morning at his home, armed with the letter from the young lady at the Library. . . We weren’t at all sure how an Artistic Temperament feels toward Tourists so soon after breakfast. In spite of the early hour, he had already gone out when we arrived, but his very beautiful wife (if that’s what she is) received us in a purple brocade dressing gown and slippers, and showed us his pictures, promising that he would return very soon. He had only about five oil paintings, as most of his time is being devoted to murals, and though our baskets seem to be most elastic in their capacity, I don’t believe that I could get a mural in. . . In the meantime, Rivera arrived home, and proved to be a great big, untidy creature, about 38 years old, with a very genial manner, a most interesting face, a perfectly child-like, pleasant smile, the worst fitting suit in the world, and little spikes of hair sticking up all over his head. He had nothing of the temperamental genius about him, and was much more pleasant than was necessary to us.

–Mancera Hotel, Mexico, April 1, 19261

By this time, Rivera was recognized as a key figure of the Mexican Renaissance, whose murals helped formulate a national art that reflected the socialist goals of the Mexican Revolution. Born in 1886, in Guanajuato, Mexico, Rivera initially trained at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts in Mexico City and worked with the political caricaturist José Guadalupe Posada, who had a decisive influence on his art.

Inspired by Renaissance frescoes, Rivera’s brand of muralism combined his conviction in the value of public art with what would become his signature earth-toned, Social Realist style. In accordance with his Marxist views, Rivera positioned the masses as the heroes of his murals, painting narrative scenes championing Indigenous Mexican culture and laborers who worked in the name of progress.

Children abound in Rivera’s murals, often depicted protected by their mothers or actively participating in the creation of a new society. The children in his easel paintings from the 1920s, such as Mother and Child, are generally removed from any specific cultural or political context and are often posed in Rivera’s studio as evidenced by the brick floors and bright blue wainscoting. As art historian Adriana Zavala has noted, such images of “beautiful Indian women” are ennobled embodiments of tradition and symbols of fertility.2

The Mexican muralism movement involved government-commissioned murals that aimed to educate the population about Mexican history and culture and foster a sense of national identity. Together with Rivera, José Clemente Orozco is considered one of the great Mexican muralists from this period and was highly impacted by the violence and suffering he witnessed during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) Like Rivera, at a young age Orozco became interested in José Guadalupe Posada’s political cartoons and was inspired to enroll in drawing classes. Although he tragically had his left hand amputated after a firework accident in 1904, Orozco continued to pursue a career in art. He worked as a caricature artist for different newspapers, mostly focusing on those suffering from social inequity and destitution.

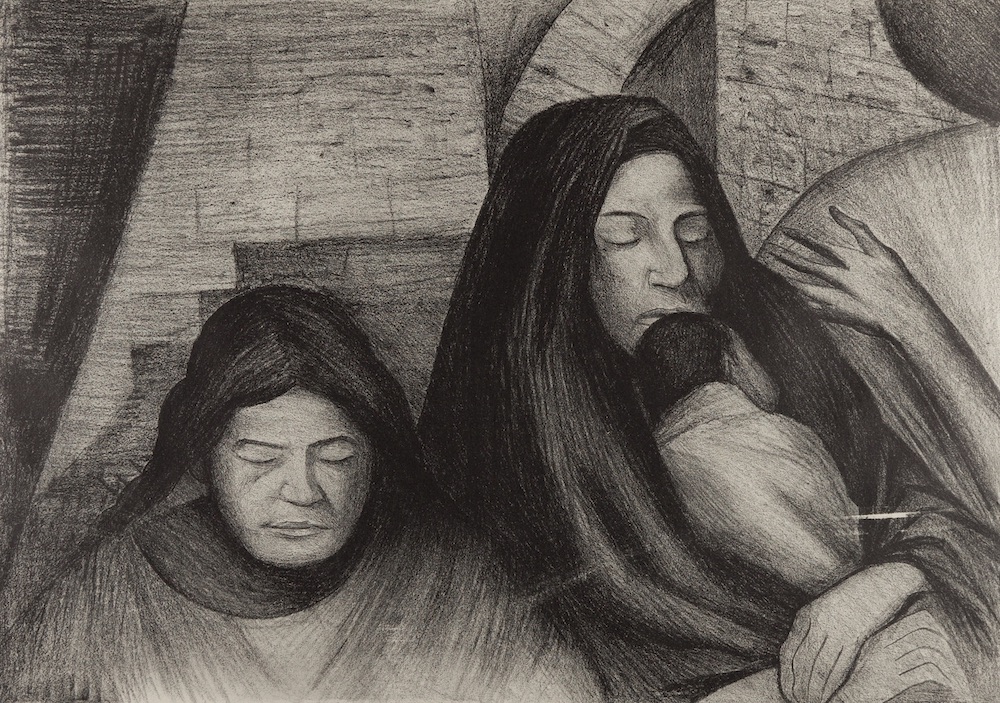

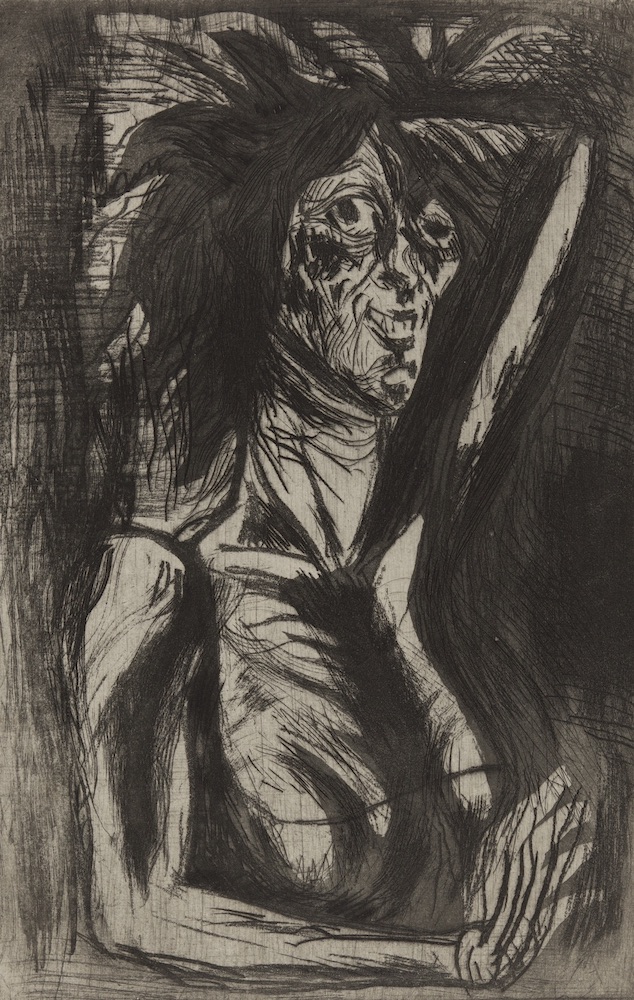

His lithograph, Three Generations, relates to Orozco’s 1926 mural The Family, completed for the National Preparatory School in Mexico City. The detail featured in this print shows a mother, child, and grandchild, emphasizing the continuity of Mexican culture. Made later in his life in 1944, La Loca depicts the darker aspects of human experience and the emotional turmoil of World War II.

Like his peers Rivera and Orozco, Rufino Tamayo helped bring international attention to Mexican art through work that reflects his pre-Columbian heritage as well as the influence of Cubism and Surrealism. Fiercely independent, Tamayo rejected the political themes of muralists like Rivera and Orozco, who were viewed as national celebrities. Instead, Tamayo focused on the formal elements of art, such as color, shape, and balance. He was greatly influenced by modern European art movements, merging those artistic approaches with themes and subjects from Mexican culture. His work often features distorted forms and exaggerated lines that heighten the emotional impact of his work, as seen in Bird Watcher from 1950. Dogs were a recurring image in his work, especially during Tamayo’s period living in New York City in the 1940s, and his animal paintings have been interpreted as an allegory for the anxiety of war.

Another pivotal figure in the modernist development of Mexican art and represented in MCAM’s collection is Alfredo Ramos Martínez. He spent his formative years immersed in the artistic life of Paris, returning to Mexico in 1910 on the eve of the country’s Revolution. After becoming director of the famed Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, he established the nation’s first open air schools and encouraged his pupils to create work that captured observations of daily life. In 1929, Ramos Martínez and his family relocated to Los Angeles. For the next two decades, his subject matter focused on the people and culture of Mexico, with the artist receiving many notable mural commissions throughout Southern California. His canvases depict Indigenous traditions, local crafts, and religious icons painted in striking hues of umber and sienna accented by bold highlights of color.

American artists were widely influenced by the work of the Mexican muralists, including Bay Area artists who met Rivera during his trips to San Francisco. Painter and printmaker Emmy Lou Packard developed a close relationship with Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo and became his principal assistant on the Pan American Unity mural he painted on Treasure Island for the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1940.

Born in El Centro, California, Packard’s father was the founder of an agricultural cooperative community in the Imperial Valley and an internationally known agronomist. In 1927, Packard traveled with her parents to Mexico for her father’s consulting job with the Mexican government working on agrarian reform issues. Packard, who was thirteen at the time, had already begun painting and drawing. While in Mexico, Packard’s mother introduced her to Rivera and Kahlo, marking the beginning of a long friendship and mentorship. Packard would later travel back to Mexico to live with Rivera and Kahlo, working as their studio assistant.

Packard’s linoleum prints celebrate everyday people—their work, history, and environment—expressing her progressive values. Her print Crab Fisherman in the museum’s collection is typical in its depiction of laborers who pick and distribute the abundance of produce and seafood cultivated in northern California.

Similarly, Pablo Esteban O’Higgins was strongly influenced by Rivera, immigrating permanently to Mexico in 1924 to assist on Rivera’s murals at the National School of Agriculture at Chapingo as well as the artist’s famous mural series at the Secretaría de Educación Pública in Mexico City. Like Rivera, O’Higgins became an active member of the Mexican Communist Party and created political illustrations and images that celebrate workers and Mexico’s Indigenous communities.

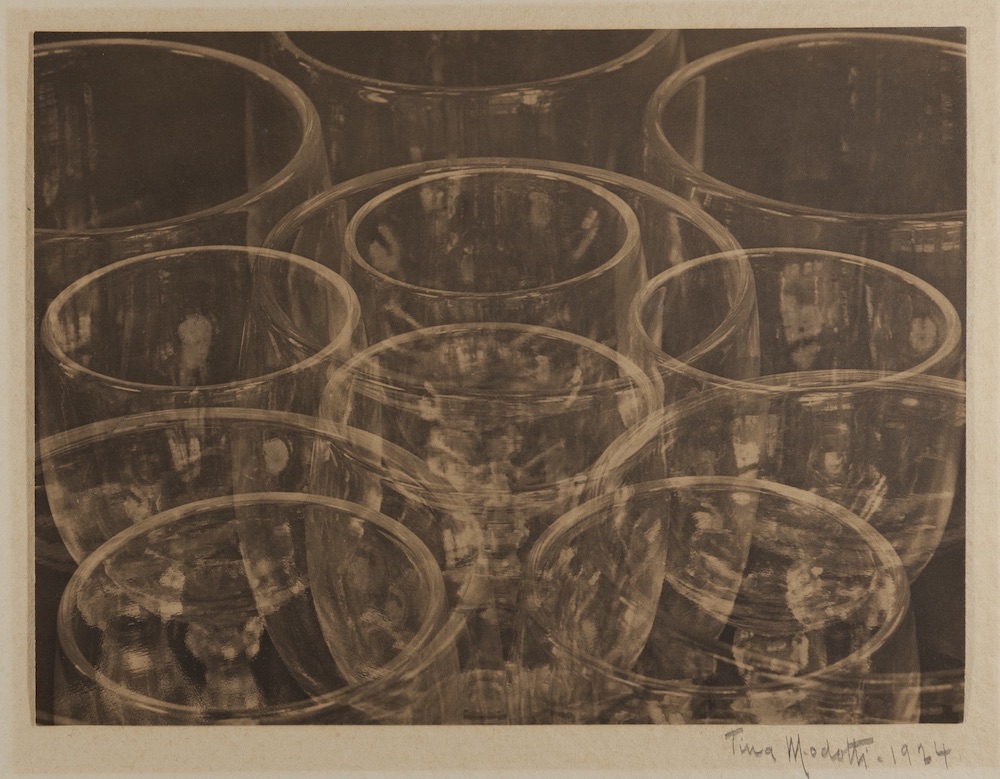

Included in this mix of American ex-pats was Italian-American photographer, model, actor, and revolutionary political activist Tina Modotti. Born in Udine, Italy, Modotti emigrated to the United States in 1913 to live with her father in San Francisco. In 1923, while romantically involved with photographer Edward Weston, Modotti relocated to Mexico City with Weston where they established a portrait photography studio. Together they found a community of political intellectuals and artists, which included Kahlo and Rivera, which subsequently led to Modotti joining the Communist Party.

During her time in Mexico, Modotti became the primary photographer for the Mexican mural movement, documenting the works of both Rivera and Orozco. She and Rivera embarked on an affair, during and after which he portrayed her in his works, including The Abundant Earth (1926) and In the Arsenal (1928). It was during this period that Modotti’s photographic style evolved, including her formal experiments with architectural interiors, blooming flowers, urban landscapes, and especially in her many beautiful images of workers during the Depression. Modotti remained involved in radical politics throughout her time in Mexico before being exiled in 1930 for her suspected involvement in the attempted assassination of the Mexican president.

While the influence of the Mexican modernists is well-documented in the museum’s collection and exhibitions, the Mills College Art Museum supported contemporary Latin American artists from a range of nationalities. The 1942 Summer Sessions program included a far-reaching group exhibition entitled Contemporary Art of Latin America, and Bolivian-born artist and education Antonio “Tony” Sotomayor was a guest instructor along with Chilean sculptor and draftsman José Luis Perotti.

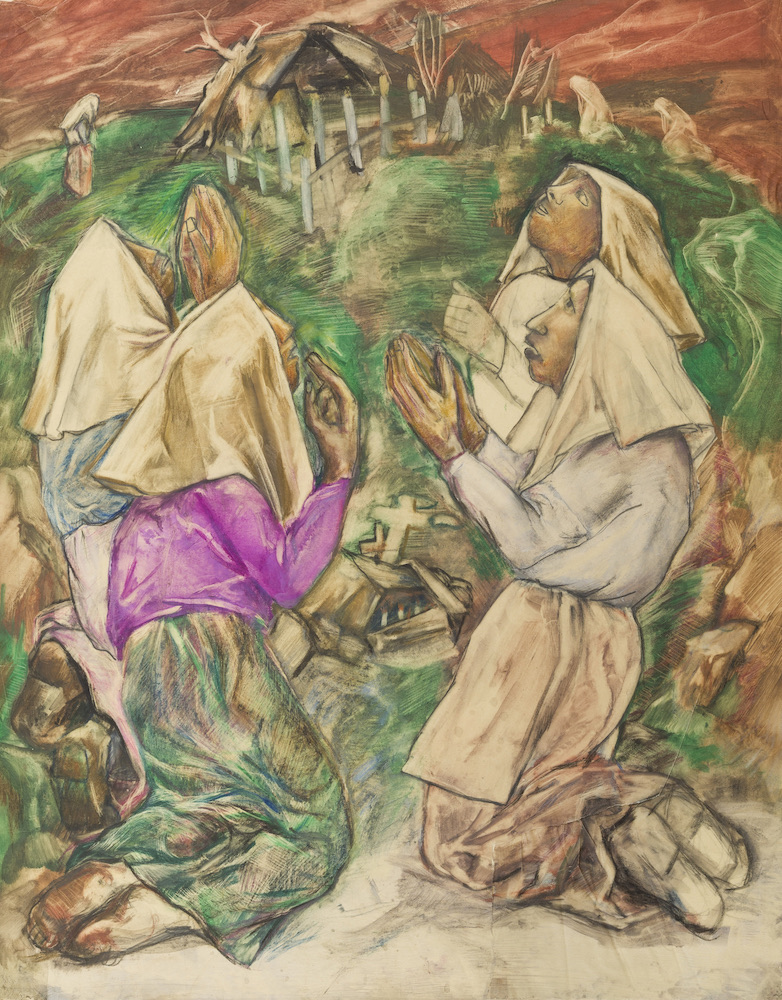

Sotomayor had arrived earlier in San Francisco in 1923 and drew inspiration from Rivera’s murals and painting. This influence is evident in Sotomayor’s images of Indigenous women and children, characterized by an emphasis on simple, geometric shapes and the broad, flat use of vivid colors. Perotti’s watercolor, Praying Women, shows the influence of the Cubist and Expressionist aesthetics championed by Orozco and Tamayo. While not as well-known as their Mexican counterparts, their inclusion in the Summer Sessions was significant in bringing Latin American modernism to the Bay Area.

NOTES