IV. Photographer and Fencer: A Golden Pair

- Jenny Varner

Imogen Cunningham, one of the most well-known and widely acclaimed photographers of the twentieth century, has her place in the history of Mills College: she is one of the many notable women associated with the school. The Mills College Art Museum (MCAM) owns over sixty of her remarkable photographs, ranging from her widely acclaimed delicate florals to portraits of luminaries of the time. Unseen: The Hidden Labor of Women explores the nature of women’s work in unconventional and often invisible areas; one of Cunningham’s photographs in particular stood out and is included in this exhibition. The photograph is a stunning 1935 portrait of Helene Mayer, who is a very accomplished Mills woman. Cunningham, a “confident, fearless, and ambitious” artist, pairs perfectly with Mayer, a world champion fencer from Germany.1 Both served as mentors to dozens of Mills students, and both refused to conform to the conventions placed on them by society’s gaze.

A woman stands straight in front of the camera in her fencing uniform with her sword partially covering the right side of her face and her helmet held partly off view, but the composition is not even the most notable aspect of this photograph (fig 15). The unwavering look Mayer gives the viewer is almost daring them to doubt her, as if nothing and no one could stop her. Although Mayer is neither off to one side nor centered, it is as if nothing else matters but Mayer’s piercing gaze. This is not just an act, she holds a remarkable tale behind her eyes that includes not only the struggles both of being a champion, but also the struggles of an exiled woman who can scarcely imagine the horrors soon approaching from her German homeland.

Mayer rose to stardom early on in her life when she won the national fencing championship in Germany at the age of thirteen, and soon found herself beloved by her country for her prodigious skill. On the rise, Mayer went on to win gold in the 1928 Olympics held in Amsterdam at only eighteen years old. Then Hitler rose to power in 1933 and everything changed; as a person of Jewish descent, Mayer lost her rights as a citizen and her bubble of fame burst “by a force that had overwhelmed her country and was spilling into the rest of Europe.”2 The United States became her new home after she painfully fled in exile when she became unwanted by her homeland.3

Years later, Mayer was still practicing fencing and watching the turmoil unfold in Germany. She was then faced with the difficult decision of whether or not to pursue participating in the 1936 Olympics held in Berlin. There was immense controversy surrounding that year’s games and its location in Nazi Germany, and arguments broke out both across the United States and the whole world. In America, those opposed to the games saw it as an opportunity to make a statement to Hitler and attempt to force the German government to cease its persecution of Jewish people.4 There were attempts to make the games fair by pushing Germany to make pledges to not partake in any discriminatory practices against Jewish athletes, and the governing bodies of the Olympic Committee decided in the end that Germany’s promises were sufficient. Of course, Germany did not actually comply with the deals they had made, and Jewish athletes were almost entirely barred from the German teams.

Mayer was denied access and membership to the local fencing clubs in Germany, but she was selected for the German team in the end. Some critics will argue that she was only selected because Germany needed to have an athlete of Jewish descent to save face at the games, and while this is likely the reason Germany allowed her to compete, Mayer more than deserved and earned her spot in the Olympics. A few critics like Les Carpenter have suggested that Mayer was selfishly placing her desire to be a champion again over the needs of the Jewish people, but I believe quite the opposite is true. Instead of allowing Germany to crush her Olympic career, Mayer stood up and won silver despite all the odds; not because she wanted to bring glory to Hitler, but rather because she knew she was one of the best fencers in the world and deserved to compete at the highest level. So, rather than an exiled woman seeking another chance for fame, Mayer took what was rightfully hers and proved that people of Jewish descent deserve to be recognized solely for their talent, not their family tree.

Named by Sports Illustrated as the “greatest fencer of the 20th century,” Mayer’s skill was barely matched, and she brought that talent and champion spirit here to Mills College where she was a language professor and fencing instructor.5 This was where she met Cunningham, the photographer who would later capture her image (figs 16 and 17). As friends, Mayer was a subject for Cunningham on multiple occasions, although her most famous photograph of Mayer is the one in Unseen. Cunningham has portrayed Mayer in a way fitting the woman she was: captivating, fearless, and a champion.

For the woman behind the camera, “portraiture would always be [Cunningham’s] first love and became her expertise.”6 Wherever she was, Cunningham could find something to photograph, from her backyard garden all the way to the streets of Paris. Her eye for photography began very early in her life and she expressed her interest in photography when she was only in high school; luckily, Cunningham was the daughter of a “free-thinking father” who encouraged her to pursue her artistic dreams.7 As a well-rounded artist, she was interested in more than just the capabilities of cameras to produce art, she was determined to know the scientific process behind the medium. To learn about this, she attended the University of Washington in 1907 and graduated with a Chemistry degree.

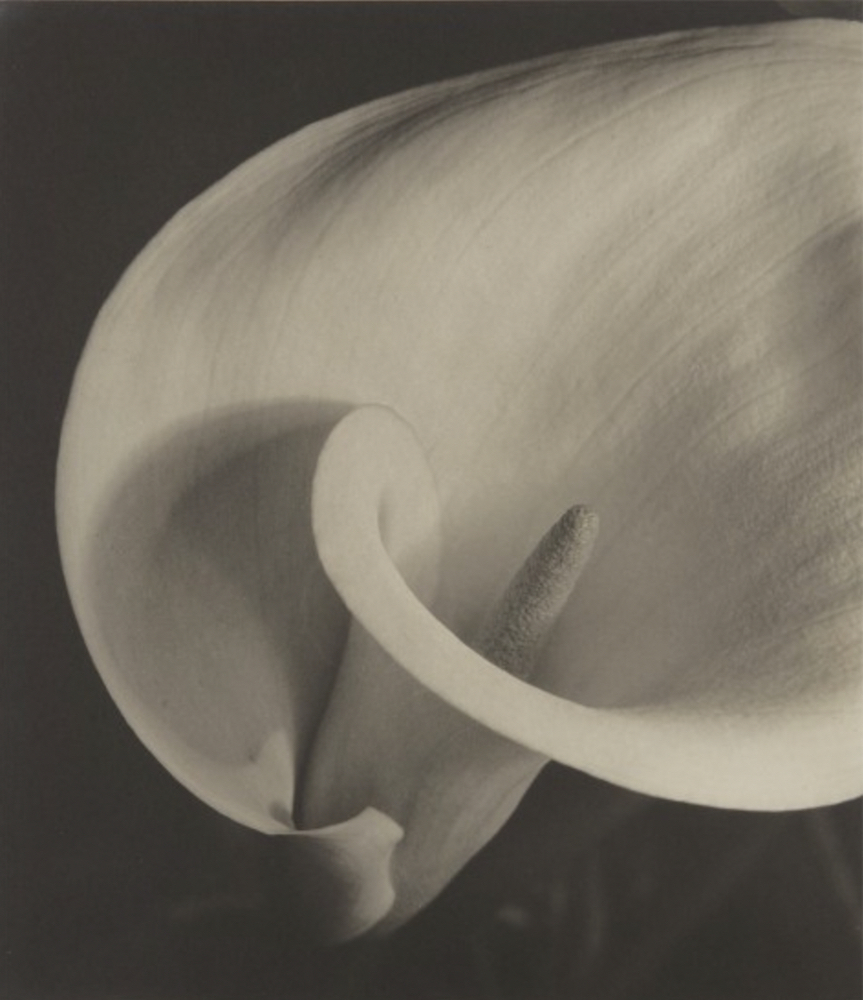

Now equipped with knowledge of every aspect of photography, she set out to find work and was first hired by photographer Edward Curtis. Throughout her artistic career, Cunningham took commercial jobs to support herself, work some of her male peers would refuse to take on principle. With the money she earned along the way, she opened “the first studio for artistic photography in Seattle” in 1910.8 Later meeting her husband, the artist Roi Partridge, she married in 1915 and had three children. During this time Partridge was traveling often which left Cunningham to raise their sons and manage the household, all while trying to maintain her studio and artistic career. But, she did not allow her role as a mother to inhibit her role as an artist, so she grew her own garden and took photographs of her own beautiful flowers; these photographs “are regarded today as historically radical and groundbreaking.”9 These botanicals are so noteworthy because by focusing her camera so closely on the flower, like in Calla, she elevates the flower beyond everyday nature photography and takes it into a realm of fantasy shapes highlighted by her keen eye for lighting (fig 18). With this, Cunningham proves that being a mother does not equal the end of a woman’s career and that mothers can hold a role in society outside of their own homes.

After moving to San Francisco with her family, Cunningham was introduced to Mills College where Partridge taught and served as the first director of the Mills College Art Museum while she quickly became an invaluable mentor to Mills students. It is here that she connected with Mayer and many other notable men and women who were prime subjects for Cunningham’s portraits. It was during the 1930s that Cunningham became acquainted with other Bay Area photographers including Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, Willard Van Dyke, and Henry Swift, and together they formed the groundbreaking Group f/64, which advocated “sharp focus, a ‘pure’ photography free of manipulation or affect.”10 Cunningham proved to be an incredibly diverse photographer as her styles and subjects changed over her decades long career, but unfortunately she was not widely acknowledged until the final twelve years of her life.

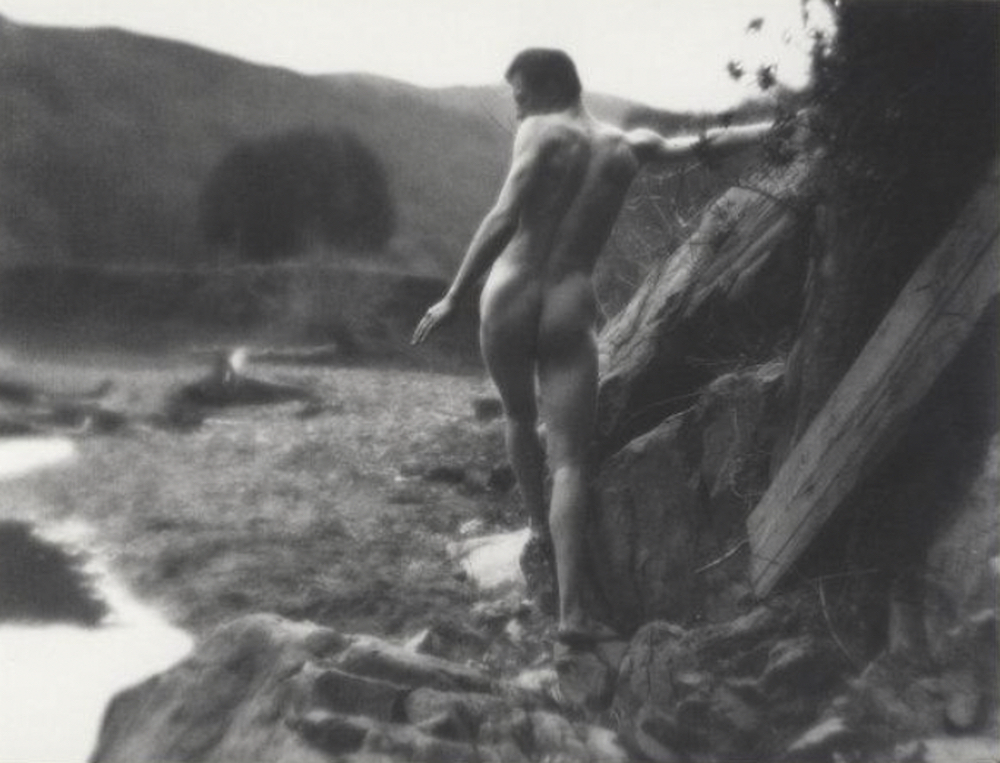

Despite her accomplishments as a female artist, Cunningham largely did not consider herself a feminist, but her career and life story are a prime example of a woman who would not let gender roles stop her from pursuing her dreams. Some of her photographs are incredibly provocative for the time as she was one of the first photographers to capture the male nude instead of only the female nude (fig 19). Despite receiving sharp criticism for this, Cunningham continued to capture nudes of both genders in which she “innovatively [abstracts] the human body into intersecting geometrical forms.”11 She was not entirely silent on feminist matters as she has mentioned the pay gap between men and women photographers on multiple occasions as well.12

Between the subject and the photographer, Helene Mayer, Fencer is a prime example of women who may not have had an openly feminist agenda, but stood up for women’s rights just by leading the lives they did. For Mayer, on the surface level her labor was physical–as an athlete–but she also dealt with the emotional impact of being forced to leave her country and later returning under the flag of a tyrant to compete for what she knew she deserved. Women in sports have struggled for a long time with equality in athletics and Mayer soared to the top of her sport and will be remembered as one of the best fencers of her age, all while being a woman dealing with intense emotional labor. For the woman who captured her spirit so well, Cunningham, faced the challenge that awaits all women artists as they jockey with male artists to take what they deserve throughout their careers. She invested so much of her time and intellect into perfecting the art of photography, all while raising a family essentially on her own. By being both a mother and a successful artist, Cunningham proved that the labor of motherhood is not always a road block.

Together these women send a powerful message proving that women can succeed under circumstances working against them, and they show how multiple forms of labor combine to shape a woman’s life. Mayer’s strong gaze draws a viewer in with the help of Cunningham’s artful composition, both working together to stand out against the struggles of the twentieth century.

-

Aidan Dunne, “Ideas and Images Without End,” The Irish Times, accessed October 31, 2021, https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/ideas-and-images-without-end-1.1199279. ↩︎

-

Les Carpenter, “Nazi Germany’s Jewish Champion: The Mystery of Helene Mayer Endures,” The Guardian, accessed October 31, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2016/jul/28/helene-mayer-nazi-germanys-jewish-champion-fencer. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

D. A. Kass, “The Issue of Racism at the 1936 Olympics,” Journal of Sport History, vol. 3, no. 3 (Winter 1976): 223. ↩︎

-

Carpenter, “Nazi Germany’s Jewish Champion.” ↩︎

-

“Imogen Cunningham,” The International Photography Hall of Fame, accessed October 31, 2021,

https://iphf.org/inductees/imogen-cunningham/. ↩︎ -

Rachel Eggers, “Imogen Cunningham Retrospective Debuts at Seattle Art Museum November 18,” The Seattle Art Museum, accessed October 31, 2021, https://seattleartmuseum.org/Documents/PR/Imogen%20Cunningham_press%20release.pdf. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

“Imogen Cunningham–Biography and Legacy,” The Art Story, accessed October 31, 2021, https://www.theartstory.org/artist/cunningham-imogen/life-and-legacy/. ↩︎

-

Alex Greenberger, “Imogen Cunningham’s Rise: Why the Proto-Feminist Photographer has Grown so Popular,” ARTnews, accessed October 31, 2021, https://www.artnews.com/feature/imogen-cunningham-why-is-she-important-1234571453/. ↩︎

-

“Imogen Cunningham–Biography and Legacy,” The Art Story. ↩︎